11

rewilding landscapes working to restore the Circle of Life.

4

species of vulture found in Europe (griffon, cinereous, Egyptian, and bearded), with all of these species found in at least one of Rewilding Europe’s rewilding landscapes.

4

species of large carnivore present in our network of rewilding landscapes (brown bear, grey wolf, Eurasian lynx, and golden jackal).

9

species of wild/semi-wild herbivores reintroduced or restocked in Rewilding Europe’s operational landscapes, comprising European bison, chamois, water buffalo, Tauros, primitive horses, Przewalski’s horses, kulan, red deer, and fallow deer.

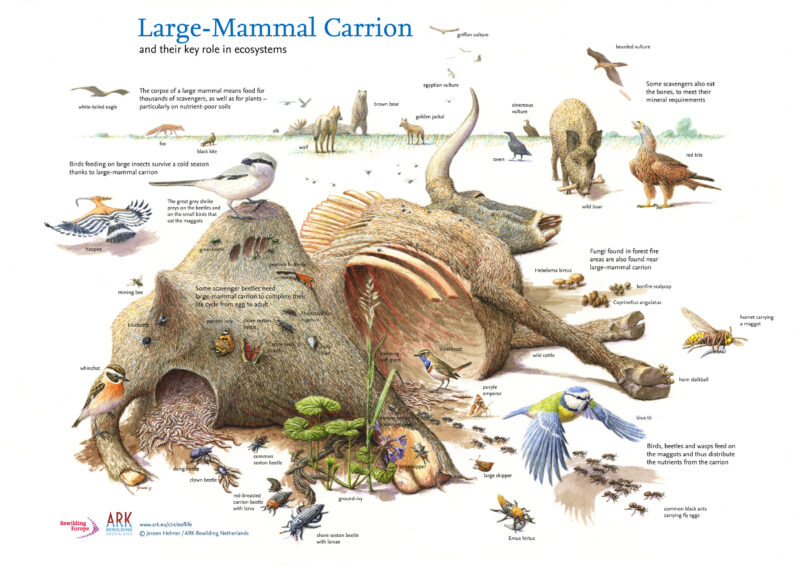

Every day, across Europe, the Circle of Life rotates in infinite complexity. Herbivores, which feed on plants, are hunted by predators. Sometimes they simply die of old age or disease. Their carcasses are also cleaned up by scavengers — such as vultures, foxes, wild boar — and an array of insects, which are, in turn, part of intricate local food webs. Eventually, aided by the action of myriad microorganisms and fungi, once living flesh is broken down and nutrients are returned to the soil, which then help new plants to grow.

The Circle of Life is also important in aquatic ecosystems, where — just like on land — scavengers and decomposers ensure that energy and nutrients from dead organic matter are recycled back into the food web. In the marine environment, species such as sharks, crabs, octopuses, and eels are common scavengers — often gathering in large numbers at “whale falls“. Processes such as the migration of Atlantic salmon — which can happen in free-flowing rivers — provide carrion that is eaten by birds, aquatic carnivores, and other fish, transferring energy and nutrients between marine and freshwater ecosystems.

Of the huge number of terrestrial and marine scavengers, vultures are the only species that feed exclusively on carrion. Capable of consuming entire carcasses in a matter of hours, they are our most powerful allies in helping to recycle nutrients, transfer energy, and reduce the risk of disease.

Despite their critical importance, the Circle of Life and role of carcasses and the scavengers that feed on them have long been undervalued. In many parts of Europe, human influence on the landscape means the circle is broken or weakened, negatively impacting wildlife populations and degrading nature’s ability to look after us. Across the continent, wild carcasses have become a rare commodity. Wilder landscapes have become agricultural land, the abundance of wild grazers is greatly diminished, and legislation demands the immediate removal of dead livestock in most landscapes. The widespread disappearance of biological “waste” from the European ecosystem has had a hugely negative impact on scavengers and food webs.

In collaboration with partners, Rewilding Europe has been working to restore the Circle of Life across Europe for more than a decade, with populations of wild and semi-wild herbivores — such as Tauros, horses, kulan, bison, chamois, red deer and fallow deer — reintroduced or restocked in many of our rewilding landscapes. As these animals become increasingly integrated into local food webs, they are boosting the availability of carrion for local scavengers, such as vultures, wolves, foxes, golden and white-tailed eagles, ravens, kites, wild boar — and a range of insects, such as butterflies and beetles. Restoring natural processes such as grazing and browsing, predation, and scavenging breathes life back into entire ecosystems, making them healthier and more resilient.

We are also directly supporting vulture populations in a number of rewilding landscapes, through measures such as reintroductions and releases to boost population and increasing the availability of food for scavengers. Efforts to enhance co-existence with scavengers, carnivores, and herbivores encompass anti-poisoning patrols, promoting lead-free ammunition, heightening the visibility of power lines, and building engagement through measures such as educational camps and workshops.

Activities related to the Circle of Life in Rewilding Europe’s rewilding landscapes through till the end of 2025. Dark purple () represents ongoing activities, while light purple (

) represents activities in their preparatory stage.

Vultures are nature’s most iconic scavengers. An essential part of the Circle of Life, they play a critical role maintaining healthy ecosystems as nature’s clean-up crew. Vultures have exceptionally strong, corrosive stomach acid that allows them to safely digest deadly pathogens like anthrax, cholera, and botulism from rotting carcasses. In addition to recycling nutrients, their ability to dispose of dead animals more rapidly than other scavengers therefore reduces the risk of bacterial and viral outbreaks that could affect other wildlife, livestock, pets, and potentially humans.

Vultures also deliver other benefits. In many places, the recovery of these majestic birds is attracting vulture watchers in growing numbers, benefitting local communities through the development of nature-based economies. They also reduce greenhouse gas emissions by rapidly consuming animal carcasses, thereby preventing the release of methane and CO2 that would otherwise occur during more gradual natural decomposition and industrial disposal.

Two centuries ago, Egyptian, bearded, cinereous, and griffon vultures were widespread in central and southern Europe. Yet a decreasing availability of food, coupled with habitat loss, persecution and poisoning, saw vultures disappear from most European countries. Thanks to reintroductions, better species protection, and changes in veterinary restrictions, European vulture populations are now slowly but steadily recovering, but continued support is critical — the birds still face multiple threats and challenges, such as illegal poisoning and a lack of food (see the section on boosting the number of carcasses available for vultures below). The isolated nature of many breeding populations and low productivity rate of the species makes the task of ensuring their long-term survival even greater.

Rewilding Europe is reintroducing vultures in a number of rewilding landscapes.

These reintroduction programmes were either started or stepped up over the last five years and will continue until 2030. We are aiming to release griffon vultures in the Southern Carpathians rewilding landscape in Romania by 2027, and are encouraging the same species to settle in the Velebit Mountains by establishing an artificial feeding station in 2025.

In the Dauphiné Alps rewilding landscape in France, Rewilding France is also supporting Vautours en Baronnies, a French NGO and European Rewilding Network member which is working to restore populations of all four European vulture species.

In 2021

a colony of cinereous vultures was discovered in the Malcata Mountains in the Greater Côa Valley rewilding landscape in Portugal.

5

Large herbivores have been reintroduced in five rewilding landscapes, where they are now part of the food web and serve as prey for carnivores and/or scavengers.

10

Self-sustaining, free-roaming populations of semi-wild horses, red deer, and fallow deer have been established in the Rhodope Mountains, as a result of animal releases carried out to boost populations over the last 10 years.

2

Human-wildlife co-existence has been enhanced in the Central Apennines and Greater Côa Valley, supporting the natural comeback of bears and wolves.

75

The number of griffon vulture pairs in the Bulgarian and Greek parts of the Eastern Rhodopes increased by 75 between 2014 and 2024.

1000+

The Rewilding Rhodopes team have released more than 1000 fallow and red deer in the Rhodope Mountains over the last ten years, in collaboration with local partners.

381

In the most recent census conducted in late 2025, 381 griffon vultures were recorded in the Rhodope Mountains. This compares to just 25 birds in 2005.

Straddling the border between Bulgaria and Greece, the eastern part of the Rhodope Mountains represents the last stronghold of vultures in the Balkans. The Rewilding Rhodopes team, in collaboration with local partner the Bulgarian Society for the Protection of Birds (BSPB), have already made significant progress enhancing the local population of griffon vultures here, which is now thriving. They have also taken steps to re-establish the cinereous vulture as a breeding species, with three releases totalling 29 birds to date. Most of these individuals are doing well and have settled in the area, with two nesting attempts in 2024 and four in 2025.

Between 2025 and 2029, at least 40 cinereous vultures will be sourced from Spain and released in the Rhodope Mountains, with the aim of establishing a permanent colony in the area. Efforts will also be made to protect and enhance a cinereous vulture colony across the Bulgarian border in Greece’s Dadia-Lefkimi-Soufli National Park.

The tagging of both cinereous and griffon vultures with GPS transmitters has been critical supporting vulture comeback, giving the local rewilding team and partners groundbreaking insight into the movement of vulture populations and the various threats that they face, such as poisoned baits, poaching, and collisions with power lines and pylons. Anti-poison dog units have been patrolling the landscape since 2016.

Keeping track of the movement and behaviour of vultures also allows us to monitor the impact of our broader rewilding efforts — offering insight into what the birds are feeding on, and what percentage of their diet is made up of the wild ungulates and grazers that we have reintroduced or restocked in a particular landscape. If the carcass that vultures are feeding on is fresh, it also allows rewilding teams to assess whether the birds are feeding on wolf kills. This is important as it shows the full Circle of Life — involving carnivores, herbivores, and scavengers — has been restored.

Efforts to support vulture comeback in the Rhodope Mountains are also focused on increasing the availability of natural food for vultures, which means they are less reliant on artificial feeding stations. The Rhodope Mountains rewilding team and the Bulgarian Society for the Protection of Birds have been working for many years to boost the availability of wild herbivore carcasses, which is helping to restore natural food webs and strengthen the Circle of Life. The partners have overseen multiple releases of red and fallow deer at various sites across the landscape, with populations of both species now increasing and gradually expanding their range.

“These efforts have already proven successful in terms of enhancing local food chains. The griffon vultures which breed in the area regularly feed on the carcasses of deer following predation by wolves.”

Carcasses play a critical role in ecosystems as they supply food to a huge array of organisms — both small and large. Increasing the abundance of large wild herbivores across Europe is important for several reasons — one of which is to enhance the availability of carcasses for vultures and other scavengers. Rewilding Europe is strengthening the Circle of Life in many of its rewilding landscapes by enhancing populations of such herbivores — and encouraging and supporting other rewilding initiatives to do the same.

The unnaturally low density of wildlife populations across much of Europe means that livestock carcasses often provide a critical food source for vultures. However, outdated EU regulations introduced after the mad cow disease crisis have limited the number of livestock carcasses farmers can leave in the field, depriving vultures of an essential resource. Although these rules were relaxed at EU level many years ago, many Member States have yet to act on this change.

In 2025, with the help of Rewilding Portugal, the first landowner in Portugal’s Greater Côa Valley was granted a license to leave livestock carcasses in the field. This milestone moment for vulture conservation will hopefully lead to the award of many more licenses, amplifying the benefits for these iconic scavengers, local farmers, and society. By helping landowners navigate the complex licensing process and advocating for policy change, Rewilding Portugal is paving the way for a future where vultures can once again thrive, in Portugal and beyond. Rewilding Europe is currently working to increase free carcass deposition in other landscapes such as the Rhodope Mountains and Iberian Highlands.

Since the 1970s, supplementary feeding stations (so-called “vulture restaurants”) have been set up in southern Europe to ensure recovering vulture populations have an adequate supply of food. Rewilding Europe itself operates such stations in the Rhodope Mountains of Bulgaria, the Greater Côa Valley in Portugal, the Central Apennines in Italy, and the Velebit Mountains in Croatia.

As a means to an end, artificial feeding stations are useful. They support the first stages of vulture reintroductions by ensuring a safe and stable supply of food for the released birds, increase the breeding success of vultures with negative population trends, and help to attract birds to new areas and encourage them to settle — which is what the Rewilding Velebit team are aiming for with their feeding station in the Velebit Mountains.

Despite their benefits, feeding stations still interfere with nature and cannot completely replace natural, randomly available carrion that would otherwise support a far more diverse range of species. This is why restoring populations of large wild and semi-wild herbivores across Europe, complemented by adequate legislation on free carcass deposition, is critical — particularly from a long-term perspective.

Beyond our rewilding landscapes, Rewilding Europe is working to help other rewilding initiatives across Europe restore the Circle of Life. Grants from Rewilding Europe’s European Wildlife Comeback Fund, for example, have supported the reintroduction of:

Various members of Rewilding Europe’s European Rewilding Network are also involved in restoring the Circle of Life:

Rewilding Europe has signed a partnership agreement with Spanish NGO GREFA to scale up the reintroduction of vultures and other bird species that play a vital role in ecosystems across Europe.

Rewilding Europe has also brought the concept of the Circle of Life closer to a wide-ranging audience, producing a Circle of Life brochure in collaboration with Dutch NGO ARK Rewilding, and through “The Circle of Life in the Rhodope Mountains” — a beautiful short documentary produced by award-winning French videographer, Emmanuel Rondeau.

In several of our rewilding landscapes, the recovery of iconic scavenging species and the restoration of food webs are supporting new business opportunities, jobs and income.

Vultures, for example, can be of great value to local communities because they support nature-based tourism, with nature lovers drawn to see these spectacular birds.

In the Greater Côa Valley, for example, vultures are playing an instrumental role in attracting tourists and sustaining the growth of local nature-based businesses. One such business is wildlife tour operator Wildlife Portugal, which received a loan from Rewilding Europe’s enterprise loan facility Rewilding Europe Capital to construct birdwatching hides. In 2025, a loan from Rewilding Europe Capital was also disbursed to Nature Madzharovo, a nature tourism company based in the Rhodope Mountains rewilding landscape in Bulgaria. Part of the money will be used to renovate wildlife hides that used for vulture watching and photography.

And in the Dauphiné Alps, in southwest France, pioneering French NGO and European Rewilding Network member Vautours en Baronnies is working to restore populations of all four European vulture species. A 2018 study found that recovering vulture populations in Baronnies Regional Natural Park and the Vercors Regional Natural Park, located a short distance to the north, were attracting more than 40,000 people annually, injecting an estimated total of 1 to 1.4 million euros into local economies.

Vultures also benefit local communities by disposing of carcasses and preventing the spread of disease, which benefits farmers, local communities, and wider society. By rapidly consuming animal carcasses, they also have a positive climate impact by reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Carnivores such as wolves are also part of the Circle of Life. Without the presence of predators such as wolves, ecosystems are less balanced, less healthy, and support less abundant wild nature — which means they are less able to deliver the benefits that humans rely on, such as clean air and fertile soil. Wolves also reduce the prevalence of diseases that affect livestock and humans, such as tuberculosis, by preying on weak animals.

Smaller organisms such as insects, bacteria, and fungi are also a critical component of the Circle of Life. These vital decomposers break down dead organic matter, recycling essential nutrients such as carbon and nitrogen back into the soil and atmosphere. This benefits people by enriching soil fertility — reducing the need for synthetic fertilisers and helping to maintain healthy forests, grasslands, and wetlands, which in turn provide myriad other benefits. This was exemplified by the release of dung beetles in the Étang de Cousseau Nature Reserve in south-western France in 2023, which was supported by the European Wildlife Comeback Fund. Decomposers also effectively manage natural waste, preventing the accumulation of dead plants and animals and ensuring the environment remains clean and functional.

Rewilding Europe’s work to strengthen the Circle of Life is part of our broader mission to make Europe wilder — and a place where people and nature can thrive together.

We are working to restore the Circle of Life in many of its landscapes by supporting vulture comeback. Support us in our efforts to rewild European skies by donating, or by visiting one of our landscapes where vulture populations are recovering through our dedicated travel booking platform, Wilder Places.