The grey wolf in Europe

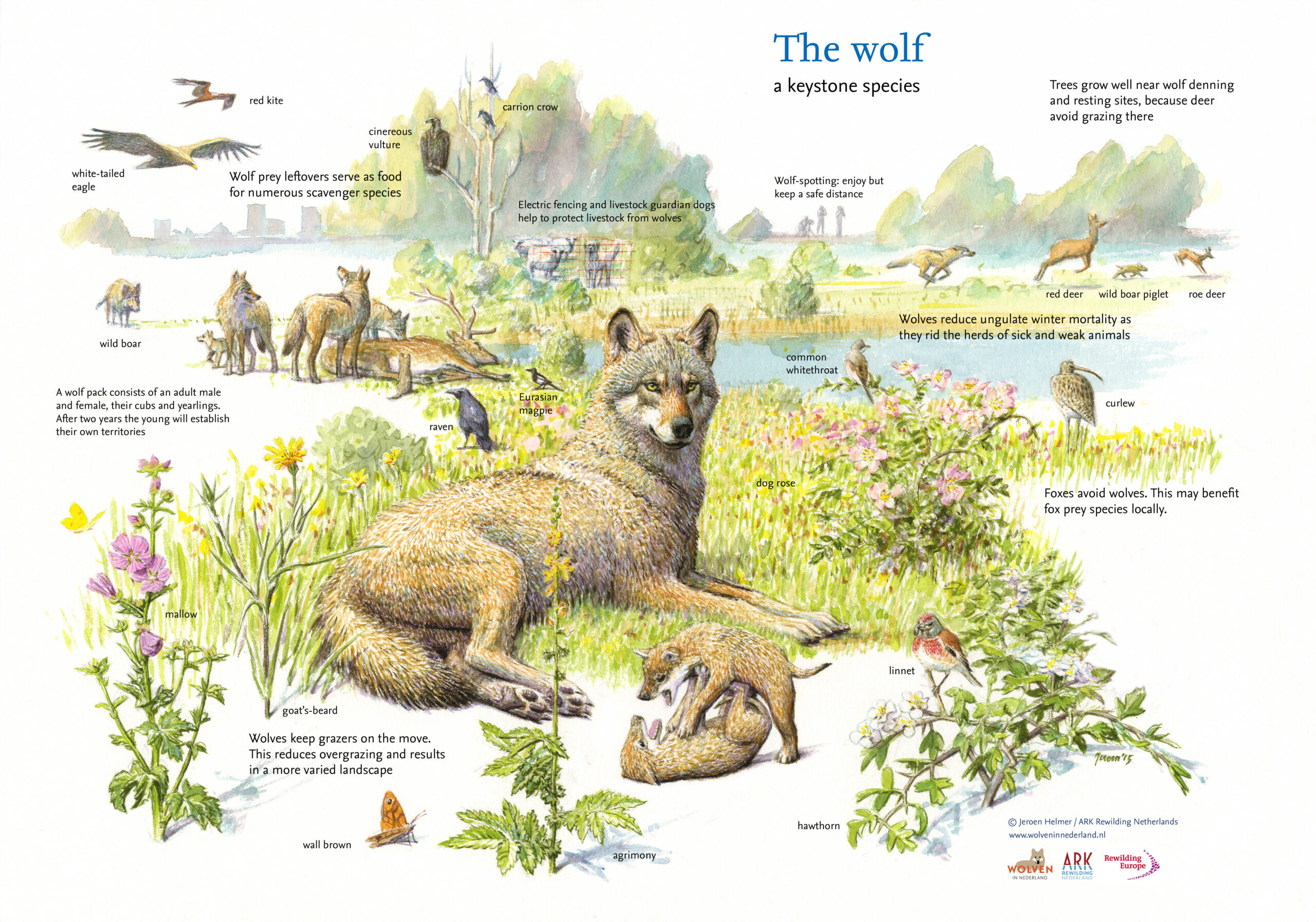

The Eurasian wolf (Canis lupus) is often portrayed as Europe’s top native predator. On average it weighs around 40 kg, with relatively short and coarse tawny fur. Wolves are highly social animals that live in extended family groups called packs. The territory of each pack is typically between 100 and 500 square kilometres. Adaptable and resilient, wolves can survive in a variety of habitats, including forests, tundra, mountains, swamps and deserts. Young wolves disperse alone over long distances, potentially travelling several thousand kilometres.

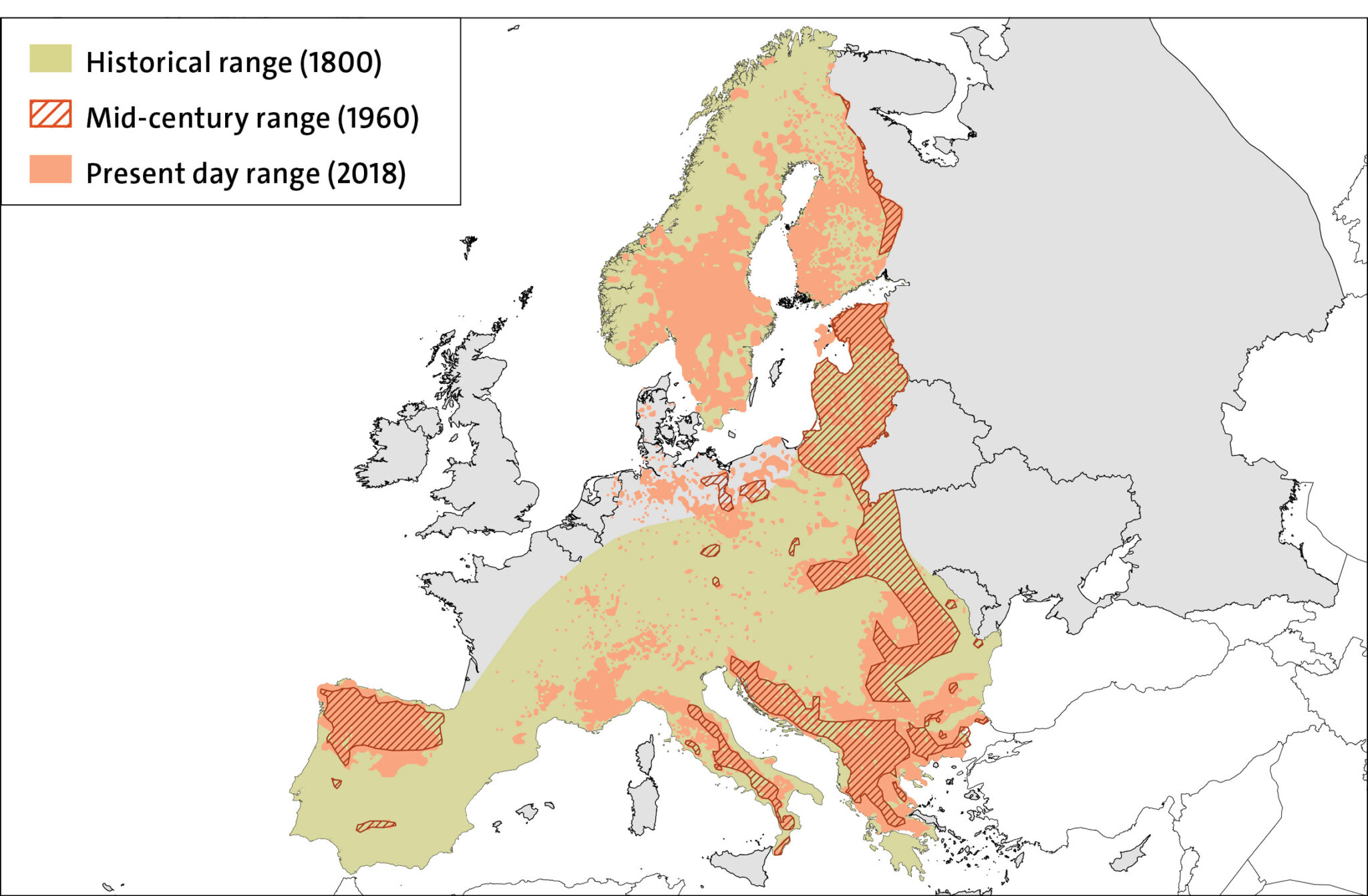

The widespread comeback of deer, wild boar and other prey species across Europe has enabled wolves to expand their range from the few places in which they were not driven to extinction (northwest Spain, southern Italy, parts of the Balkans, and Polesia). Wolves are nature’s way of restoring the balance following the expansion of wild herbivore populations.