Wolves are ecologically important animals that benefit people and nature. Rather than reducing the wolf’s protected status, the European Commission should focus its efforts on encouraging and enabling better livestock protection.

Focusing on the facts

Last week, the European Commission announced plans to review the protection status of the wolf in Europe, citing “real danger” to livestock and human life. Despite the myths and sensationalist headlines, wolves pose no significant risk to humans. In fact, Europeans are far more likely to be injured by cows than they are by wolves. According to a report titled “Wolf attacks on humans: an update for 2002-2020” by the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, the risks associated with a wolf attacking a human are “above zero, but far too low to calculate”. In reality, wolves are afraid of humans, and will go out of their way to avoid them.

While it’s true that Europe’s wolf population is now on the increase – and the species is recolonising parts of its former range – changing the protection status of the species is misguided at best, and dangerous at worst. If it really wants to address the challenges related to the return of wolves, the Commission needs to examine the facts, rather than grandstanding and issuing press releases riddled with inaccuracies.

The livestock challenge

The situation with livestock is different. Predation on livestock is the main challenge to coexistence with wolves in Europe, and across the world. It is a serious conservation challenge that can result in retaliatory killings of wolves via legal and illegal shooting and trapping, as well as the use of illegal poison baits which have a devastating impact on many other endangered species, and potentially humans and pets.

Wolves kill between 30,000 and 40,000 European livestock animals annually, of which the majority are sheep. As a result, around 8 million euros are paid in compensation to European livestock farmers each year. From an economic perspective – and in comparison with the multi-billion subsidies for agriculture in Europe distributed through the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) – this is a drop in the ocean. The livestock predation challenge is exacerbated by the fact that many European landscapes have little or no natural prey to sustain wolves. This means they are often highly dependent on livestock as a source of food (this is particularly the case for wolves that are dispersing), which complicates the development of effective and widely supported conservation solutions.

Towards a science-based approach

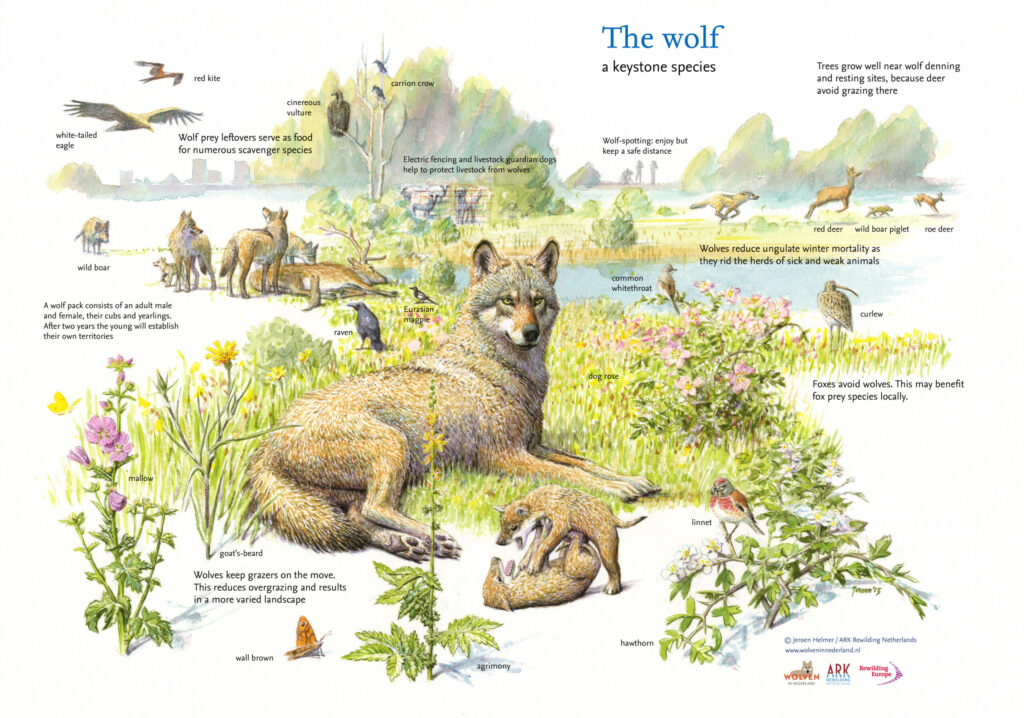

Concerns over wolves and livestock predation in Europe clearly need to be addressed. Yet the ill-conceived approach of simply eradicating wolves – by making killing them easier – is expensive, frequently unfeasible, and means we lose the wide-ranging benefits that this iconic and ecologically important keystone species can delive.

On top of this, there is evidence that killing wolves to reduce predation may not even have the desired effect, increasing the risk of predation in neighbouring areas and leading to the dispersal and weakening of wolf packs, which in turn can actually increase livestock predation. Last but not least, changing the protection status of the wolf in Europe may result in more people leaving out poison baits, which would be disastrous for wildlife (particularly for scavengers such as vultures) and perversely increase the risk of human fatalities.

“European wolves are currently doing well, which is great news because they help to restore ecosystem balance,” says Rewilding Europe’s Head of Landscapes Fabien Quétier, who has been interviewed widely on the wolf in Europe recently as an expert on coexistence. “As they return, it absolutely makes sense for there to be some flexibility on how to manage their comeback, particularly in areas where they haven’t been seen for decades. Yet that flexibility is already there within the existing policy framework. What we are seeing with the European Commission’s announcement is the wolf being hijacked for short-term political gain.”

“What we actually need is smart, science-based decision-making that reflects the reality on the ground. There are simple and effective ways to manage the threat that wolves pose to livestock and to enhance coexistence that are more effective and realistic than deliberate extermination. Prevention is the key word here.”

Livestock owners on the front line

We cannot promote coexistence with wolves and support the presence of carnivores across Europe without supporting the people who are adversely affected by their presence. Many owners of livestock and kept animals are already making efforts to live alongside wolves – without resorting to killing them – and this needs to be recognised and applauded.

“When you’ve had multiple animals killed by wolves it can be a very traumatic experience,” says Fabien Quétier. “I would like to see more empathy and support for livestock owners who are dealing with the return of the wolf on a day-to-day basis. European wolves need to be out and about in nature and doing their thing, but they shouldn’t be eating livestock. Wolves need to encounter a strong border when they encounter livestock, because they are smart, and they learn, and they will always go for the easy option when it comes to predation.”

Practical yet underutilised solutions

Quétier believes that livestock predation can effectively be minimised by protecting livestock at night in corrals, using wolf-proof fences, ensuring somebody is watching over free-roaming livestock, and particularly by deploying guard dogs – a practice which is already happening in many places across Europe. The Rewilding Portugal team, for example, are supporting the use of guard dogs in and around the Greater Côa Valley as part of a range of measures to improve human-wolf coexistence.

“These measures are established practical solutions that have been proven to improve coexistence,” says Rewilding Europe’s Head of Landscapes. “This is what the European Commission should be focusing their efforts on, rather than selling the illusion that predation by wolves can somehow be prevented by shooting them.”

EU and national guideline documents, good practices, and tools are available to prevent and compensate for the economic damage caused by wolves. Such practices include the training of dogs to protect herds, education of herders, and tools and technical solutions to deter wolves.

The European Union Guidelines for State Aid in the agricultural sector allow EU Member States to grant full compensation to farmers for damage caused by protected animals, such as wolves. This also makes it possible to fully reimburse costs of investments made to prevent such damage, such as the installation of electric fences, acquisition of guard dogs, and hiring of shepherds. In addition, financial support available through the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) can also enhance coexistence, notably via investments and increased payments for areas where the presence of large predators may have a negative impact on beneficial grazing. All of these support mechanisms are currently being underutilised, which is why we are calling for a full and long-term commitment to livestock protection in Europe.

Thinking ahead

European livestock owners need to be empowered to adapt their production systems to make them less vulnerable to wolf attack, with rural development bodies playing a more supportive role. This adaptation needs to be carried out in areas where wolves may appear in the near future, as well as those where the species has already returned to the landscape. Too often, authorities wait for conflicts to get out of hand before intervening, when they should instead be helping livestock owners to anticipate upcoming challenges.

“A good livestock protection dog takes two to three years to train, to grow up with livestock around, and to become autonomous,” says Fabien Quétier. “So the sooner a livestock owner starts embedding dogs within his or her operations the better. Proficiency in dog management and training also has an important role in determining the dog’s effectiveness. Wolf-proof fencing is another really good measure that can be employed in many situations and is readily available.”

In conjunction with raising awareness and delivering financial and technical support to livestock owners efficiently, the European livestock guard dog industry needs to be expanded and developed further.

“The effectiveness of livestock guard dogs has already been proven across the world,” says Quétier. “Livestock owners might be sceptical at first, but once they see how these dogs work, they’re sold. But European farmers need to have access to good dogs. A reliable supply of good dogs, together with training for farmers, would enhance human-wolf coexistence in Europe significantly.”

The bigger picture

Vilification of the wolf as a dangerous predator is nothing new. Measures such as guard dogs and electric fences can effectively protect livestock from predation, but they can’t directly change the way people feel about wolves. As the recent announcement from the European Commission so ably exemplifies, misconceptions, fear, politics, conflicting interests, and disinformation continue to influence the way wolves are managed in Europe today.

Attitudes towards wolves in Europe vary widely, which means measures to improve human-wolf coexistence often need to address the underlying drivers of conflict. Effective communication and transparency can ensure factual accuracy, win hearts and minds, mediate disputes, and help to achieve just and sustainable conservation solutions. We are far better off with wolves in Europe, which is why Rewilding Europe, individuals, and organisations across the continent are working hard to demonstrate how and why we could and should live alongside these iconic and beneficial animals.