Monitoring of raptor species in the Faia Brava Nature Reserve and Côa Valley Special Protection Area (SPA) shows griffon vultures have made a dramatic return to the Western Iberia rewilding area since the 1990s. This bodes well for ongoing rewilding efforts here.

Population progression

Over the last two decades northeast Portugal’s Côa Valley has witnessed a spectacular comeback by griffon vultures. This ongoing trend, together with the stabilisation of the area’s Egyptian vulture population, highlights the rewilding potential of this beautiful area and offers encouragement to the Rewilding Western Iberia team now engaged in efforts to restore wild nature here.

Portuguese NGO Associação Transumância e Natureza (ATN), Rewilding Europe’s partner in the Western Iberia rewilding area, has been closely monitoring the populations of raptor species in the 850-hectare Faia Brava Nature Reserve and 20,630-hectare Côa Valley Special Protection Area (SPA) since 2000. The SPA, which was created in 1999, wholly contains the reserve, which was created in 2000. Species monitored comprise the griffon vulture, Egyptian vulture, black stork, Bonelli’s eagle, golden eagle and Eurasian eagle owl.

It is the Côa Valley SPA’s griffon vulture population which has displayed the most dramatic variation in recent times. During the 1990s there were fewer than 10 nesting pairs of these magnificent birds located here. By 2015, with Faia Brava acting as a core area, that number had reached 74, with around 60 couples located inside the reserve.

In contrast to the griffon vulture, the SPA’s Egyptian vulture population has remained relatively stable in recent years, with some nesting sites abandoned and others occupied for the first time. In 2016, seven couples were nesting in the SPA, of which four were located inside Faia Brava.

Unlike the griffon vulture, which lives in colonies, Egyptian vultures typically nest in solitary pairs and exhibit strongly territorial behaviour. This may constrain populations in specific areas, even though potential nest sites are available.

Demographic drivers

While no formal analysis of the reasons for the griffon vulture comeback has yet been conducted, the reasons are likely to be manifold. Chief among these is the creation of a secure and conducive breeding environment with the establishment of the SPA and Faia Brava reserve. With extensive areas of steep cliffs, the site boasts prime vulture nesting habitat.

Another contributory factor is almost certainly related to bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, or “mad cow disease”), which has been on the decline in Europe for many years. In 2001, after the BSE crisis, the European Union prohibited the abandonment of livestock carcasses in fields. This had a huge impact on vulture populations, which relied on such carcasses in the absence of wild herbivores.

The subsequent relaxation of EU legislation allowed such carcasses to once again be left in nature (under special conditions), but not all European countries chose to implement this change. Until 2017 (when Portuguese legislation was finally changed), this meant that farmers were leaving carcasses in large swathes of the Spanish countryside, yet their Portuguese counterparts were still removing them (in reality Portuguese farmers are still removing carcasses today due to bureaucratic complications). This disparity was graphically highlighted in recent research, which showed GPS-tracked griffon and Egyptian vultures on the Iberian peninsula almost exclusively shunning Portuguese territory.

Fortunately for the vultures of Faia Brava, a feeding station was established here in 2007 (it was relocated outside of the reserve to the Côa Valley SPA in 2017). This feeding station is licenced for the deposition of food, with the specific goal of providing supplementary food for Egyptian vultures. Feeding takes place between March and August (during the breeding season and coincident with the stay of this migratory species in Portugal). Small pieces of discarded meat from local butchers are typically provided, which favours Egyptian vultures rather than griffon vultures, which prefer whole carcasses.

As a means to an end, feeding stations (or so-called “muladares”) are undoubtedly useful. Yet they still interfere with nature and cannot completely replace natural, randomly available carrion that would otherwise support a far more diverse range of species. In an ideal world, scavengers are entirely supported by natural prey and carcasses.

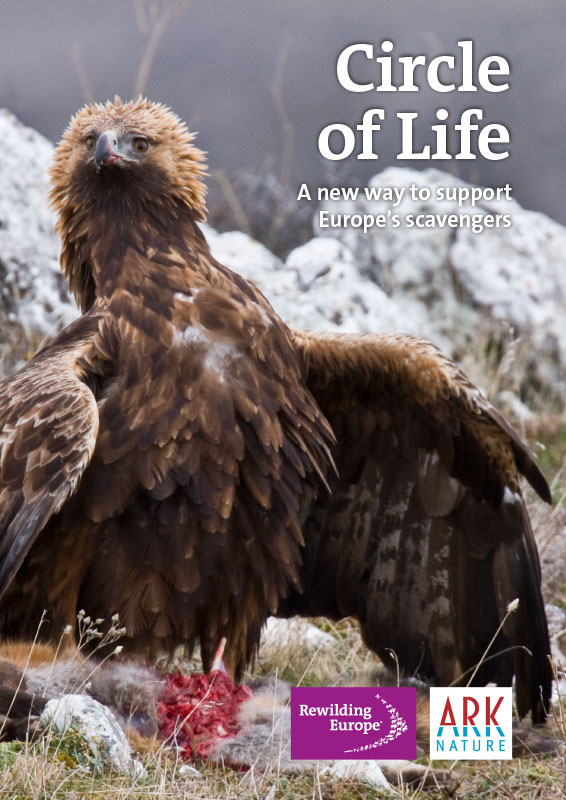

This is the objective of the Circle of Life, a new approach to the management of herbivore carcasses presented by Rewilding Europe and ARK Nature last year, and the reason why Rewilding Europe is introducing a growing number of wild herbivores, such as wild horses, into Faia Brava and the SPA.

Threats and opportunities

The expansion of the griffon vulture population in Faia Brava and the Côa Valley SPA has had a range of consequences. Black storks and Bonelli’s eagles are increasingly being outcompeted for nesting sites, forcing them to relocate to less ideal territories. The ATN survey has revealed eagles relocating away from Faia Brava.

“It is important to monitor and control actions that greatly benefit the griffon vultures, such as supplementary feeding, in order to avoid side effects on other susceptible species,” says Sara Aliácar, ATN’s conservation officer and project coordinator.

The Western Iberia rewilding team has recently been involved in artificial nest building to help threatened species such as black storks and Bonelli’s eagles. Through habitat restoration efforts the team is also working to boost the populations of prey species, such as pigeons, red-legged partridges and rabbits for the eagles. The creation of artificial ponds should hopefully provide more food for the storks too.

Griffon vultures who move outside Faia Brava are also more likely to encounter veterinary diclofenac, a drug used to treat livestock such as cows and pigs. When livestock carcasses are left in nature, vultures feed on them, ingest the diclofenac, and are poisoned and die. A dose of just 0.1-0.2 mg/kg body weight can rapidly induce lethal kidney failure in the birds. In April 2018 the Portuguese government recommended a cessation of the use of diclofenac, but it is still not illegal.

Other threats to raptors in the Côa Valley include poisoning, electrocution from power lines and natural fires, although instances of the former are now on the decline. The Rewilding Western Iberia team and ATN are heavily involved in environmental education and fire surveillance, while an anti-poison dog unit has also been established by an associated

By reintroducing semi-wild herbivores such as wild horses and Tauros, Rewilding Europe and its local partners are significantly reducing the risk of fire in the Western Iberia rewilding area. Natural grazing by these species leads to the creation of more diverse mosaic landscapes, with open spaces that act as effective firebreaks.

On another positive note the presence of raptors in the Côa Valley – especially vultures – is boosting the local nature-based economy. A growing number of domestic and overseas tourists are visiting the area, as well as schools.

“As a result of their comeback, more and more people are appreciating vultures as the fascinating and majestic species that they are,” says ATN’s Aliácar.

Loans from Rewilding Europe Capital, Rewilding Europe’s pioneering enterprise facility, have so far helped a quartet of nature-based businesses become established in and around Faia Brava. Wildlife Portugal, a nature-based tourism company, opened its second hide in the reserve in 2017, with vultures the star attraction. Vulture watching experiences are also offered through the European Safari Company.