With an informative publication, Rewilding Europe and ARK Nature present a new way to support Europe’s scavengers.

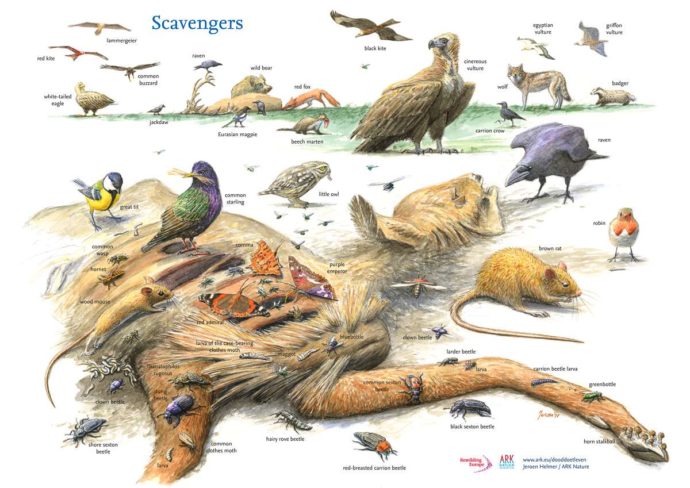

As a vulture’s head disappears inside a carcass, a beech marten bares its teeth at a red fox intent on taking a bite of the same carrion. A closer look reveals a diverse cleaning crew of beetles and flies working diligently to process what is left of the large mammal. This typical scavenging scene should be a common sight across much of Europe.

But across our continent today, wild carcasses have become a rare commodity. Wilderness has become arable land, populations of wild grazers are often managed at low densities, and legislation demands the immediate removal of dead livestock. As a result, much of the biological “waste” has disappeared from the European ecosystem and is no longer part of the natural cycle of life. Denied a natural food source, populations of scavengers are decreasing and dying out.

Rewilding Europe, together with Dutch NGO ARK Nature, now want to help Europe’s scavengers by encouraging a fresh look at how herbivore carcasses are managed across the continent. This new approach, presented today on International Vulture Awareness Day, is called the Circle of Life.

“Through adoption of the Circle of Life, we want to see large carcasses retake their place in nature, allowing Europe’s numerous scavengers to once again eat their fill,” says Frans Schepers, Rewilding Europe’s managing director.

A Circle of Life brochure provides a practical overview of the possibilities for such an approach, addressing relevant stakeholders such as those managing nature, fauna and roads. The background information it contains is intended to inform policymakers, as well as other parties interested in expanding their knowledge about this fascinating, essential and often overlooked link in the food chain.

The fall and rise of vultures

Vultures are perhaps the most iconic examples of European scavengers; the sight of these majestic birds soaring overhead on thermals or feeding at a carcass can be truly captivating.

Two centuries ago, Egyptian vultures, bearded vultures, black vultures and griffon vultures were among the most common breeding bird species in central and southern Europe. Yet the decreasing availability of food, coupled with habitat loss, persecution and poisoning, then saw vultures disappear from most European countries (Portugal, France, Italy, Austria, Poland, Slovakia and Romania). At their lowest point, in the 1960s, there were only 2,000 pairs of griffon vultures and 200 pairs of black vultures left in Spain.

Thanks to reintroductions and species protection, European vulture populations are now slowly but steadily recovering. In many regions, vultures soaring the sky has become a common sight again. Yet as the occurrence of wild herbivore carcasses has declined, so these magnificent birds have become increasingly dependent on the carcasses of domesticated animals. But stricter veterinary regulations mean this food source has also become increasingly unreliable.

Natural vs artificial

Since the 1970s, so-called supplementary feeding stations have been set up in southern Europe (and Africa) to ensure the vultures have an adequate supply of carrion. These stations now contribute to the survival of many vulture populations, and have been important in the reintroduction of vultures (for example in the Grands Causses, French Alps and Pyrenees).

As a means to an end, such so-called “vulture restaurants” are useful. Yet they still interfere with nature and cannot completely replace natural, randomly available carrion that would otherwise support a far more diverse range of species. In an ideal world, scavengers are entirely supported by natural prey and carcasses.

A perfect example is the reintroduction of the bearded vulture in the Alps, which started 30 years ago. At the beginning, birds had to be fed artificially. But with the simultaneous growth of Alpine ibex and Alpine chamois populations, the bearded vulture population here (currently some 20 breeding pairs) is now almost completely sustained by the naturally occurring carcasses of these herbivores.

Similarly, research has shown that in the Eastern Rhodope Mountains, on the Greek-Bulgarian border, the increasing griffon vulture population is sustained significantly (around 60% of the time) by the carcasses of wolf kills. Restoring food chains in this area is a flagship project of Rewilding Europe, supported by the European Commission (LIFE Vultures).

Closing the circle

The concept of scavenging involves subjects that are naturally repellent to many people: carcasses, dead animals, road kills and putrid meat. Yet for scavenging species, the availability of these things is key to their survival.

Going forwards, Rewilding Europe will continue its work to support vulture populations in three of its areas – Bulgaria’s Rhodope Mountains, the Velebit Mountains of Croatia, and in Western Iberia. While artificial feeding may have a role to play here, our main focus will always be to help scavenging species – across all our operational areas – by boosting the availability of wild herbivore carcasses and thereby closing the circle of life.

Increasing the availability of such carcasses can be achieved both by enabling wildlife comeback, and by reintroducing species – such as red deer, bison and wild horses – that would, if not for human interference, be part of the local ecosystem. In many areas, the presence of scavenging species such as vultures can be used as a basis for developing a local nature-based economy that benefits both man and wild nature.

In the Rhodope Mountains, Rewilding Europe’s local team is now working with partners to have the area’s growing herd of Konik horses legally recognised as wild animals. This will enable their carcasses to be left in nature, rather than removed for disposal. And we will continue to promote the Circle of Life, sharing expertise on best practice in supporting scavengers through the European Rewilding Network, many members of which have hugely valuable experience in this area.

In the Rhodope Mountains, Rewilding Europe’s local team is now working with partners to have the area’s growing herd of Konik horses legally recognised as wild animals. This will enable their carcasses to be left in nature, rather than removed for disposal. And we will continue to promote the Circle of Life, sharing expertise on best practice in supporting scavengers through the European Rewilding Network, many members of which have hugely valuable experience in this area.

Rewilding Europe and ARK Nature encourage anyone with an interest in conserving and boosting our continent’s hugely valuable and iconic populations of scavenging species not only to read the Circle of Life brochure, but to join with us as we take practical steps to close the circle across Europe.

Learn more about Rewilding Europe’s work with vultures in Bulgaria’s Rhodope Mountains here and Western Iberia here.