The results of the four-year study, which focused on the feeding behaviour of reintroduced European bison, Konik horses and Highland cattle in and around the Kraansvlak reserve in the Netherlands, have important implications for rewilding initiatives across Europe.

A study in grazing

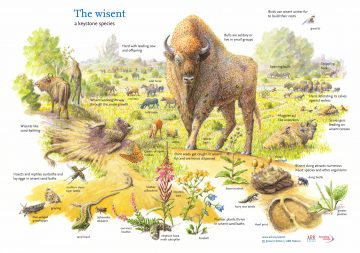

One of Rewilding Europe’s key objectives is the restoration of trophic cascades. These rely on the presence of a variety of species across a fully functioning food chain, including large herbivores that once roamed across Europe but now mostly exist in domesticated form. In Rewilding Europe’s pilot areas, the idea behind reintroducing grazers such as European bison, wild horses and Tauros is to reestablish these trophic cascades and thereby support the development of self-regulating, biodiverse ecosystems.

A four-year study, carried out between 2008 and 2012 in the Kraansvlak reserve and adjacent area also in Zuid-Kennemerland National Park, provides some of the first empirical data concerning the diet of Europe’s three largest grazers – European bison, cattle and horses – living under similar conditions in a heterogeneous landscape. The study, which has implications for rewilding initiatives and the further reintroduction of wild herbivores across Europe, was summarised in a recent research article published in the Journal of the Society for Ecological Restoration.

European bison, Konik horses and Highland cattle have all been reintroduced into Kraansvlak, a 330-hectare area of coastal dunes located west of Amsterdam, with the bison forming part of Rewilding Europe’s European Wildife Bank. The study examined the feeding behaviour of bison and horses (in Kraansvlak) and Highland cattle, which had been temporarily relocated to a nearby location in the Zuid-Kennemerland National Park. The landscapes in both locations were characterised by a large variation in vegetation, comprising dunes, grassland, patchy forest and shrubland.

The results of the study revealed that rewilding with European bison, horses, and cattle can work without supplementary feeding, even in relatively small nature reserves (none of these grazing species are given food in Kraansvlak/Zuid-Kennemerland). They also showed that all three species mainly feed on grasses and herbs. Cattle and bison included a significant proportion of woody plants in their diet throughout the year, where horses strictly grazed on grasses. However, while the bison preferred to debark trees in the winter and spring, the cattle browsed on twigs.

Implications for rewilding

Today the European bison is making a comeback from near extinction in the early twentieth century, with a current total population of around 7000 individuals. As the species has been absent from European landscapes for so many years, most of what we know about the animal’s ecology comes from studies carried out in forested areas such as Bialowieza in Poland and Belarus, which is currently home to world’s largest bison population. This means there are still large gaps in our knowledge.

“The Kraansvlak project is one of the very first to study European bison in a far more open landscape, where it now lives alongside other herbivores,” says Yvonne Kemp, Rewilding Europe’s European Rewilding Network (ERN) Exchange Officer and Project Coordinator of the Kraansvlak Bison Project, who also collected data for the Kraansvlak study and co-authored the article.

“Contrary to much expert opinion and most current management practices, our experiences and findings show that the European bison is perfectly capable of living in half open areas without any supplementary feeding,” she continues. “The study also establishes that there are subtle yet clear differences in the foraging behaviour of bison and cattle.”

So what does all this mean for rewilding and the ongoing restoration of European bison populations?

The Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan for European Bison (IUCN 2004) calls for the continued reintroduction and reestablishment of free-ranging populations across the historical range of the species. Yet when the plan was drawn up, the bison was still considered to be primarily a forest dweller.

“This study reinforces the changing view of the European bison,” says Rewilding Europe’s Rewilding Director Wouter Helmer, who recently attended a meeting of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) in Amsterdam to discuss updating the plan. “We can see that in an ideal world these animals prefer to inhabit a mosaic landscape of open grassland and forest. As we look to boost the European bison population further, the new plan should reflect this.

“Right now there is a lack of release sites for reintroducing European bison across Europe,” he continues. “The fact that these animals can live in relatively compact, diverse habitats alongside other herbivores, rather than competing with them, means that far more sites can be considered suitable for bison reintroduction.”

While further work in this area is required, the data provided by this study is also important for rewilding initiatives that aim to restore communities of grazers.

With European bison now present in Kraansvlak for 10 years, a Bison Congress was held at the reserve in October last year. This was attended by members of the Southern Carpathians-based LIFE Bison project in which Rewilding Europe participates, as well as rewilding projects from Rothaargebirge in Germany, Veluwe in the Netherlands and Lille Vildmose in Denmark, all of whom are members of the ERN. Attendees discussed a range of bison-related topics, including the insight gained from the Kraansvlak reintroduction and future management of the species.