A new way of evaluating rewilding progress has been developed by Rewilding Europe and partners. Its groundbreaking application across seven of Rewilding Europe’s operational areas – which has just been detailed in a new scientific paper – has revealed both positive impact and challenges to upscaling.

Groundbreaking application

Over the last decade, rewilding has emerged as an immediate, pragmatic, scalable and cost-effective way of restoring natural processes and enabling wildlife comeback across large-scale European landscapes, supported by trends in human demographics, associated changes in land use, and the ongoing recovery of key wildlife species. To ensure rewilding continues to grow – and to scale it up as quickly and effectively as possible – it is critical that the impact of rewilding can be easily, accurately and comparably measured.

The application of a recently developed way of measuring rewilding progress, the details of which are outlined in a paper published in scientific journal Ecography on September 1, is a huge step forward in this regard. Authored by Rewilding Europe’s Rewilding Researcher Josiane Segar – together with rewilding experts from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and other European institutions – the paper discusses the first time application of this methodology to seven of Rewilding Europe’s operational areas. The results generated reveal that encouraging progress has been made at site level, but that challenges to upscaling also exist.

From theory to practice

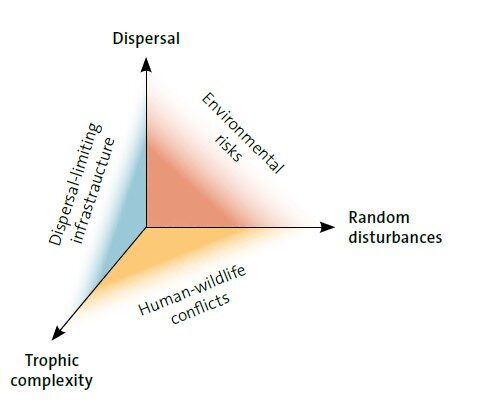

The new Ecography paper builds on an article published in the journal Philosophical Transactions B in 2018, which first introduced a three-axis framework for monitoring rewilding. Co-researched and developed by Rewilding Europe, this framework condenses ecological recovery into three key components (see Figure 1):

- trophic complexity: a measure of the complexity of relationships in a food web

- random natural disturbance: caused by natural events such as wildfire or flooding

- dispersal: how easy is it for species to spread out across landscapes

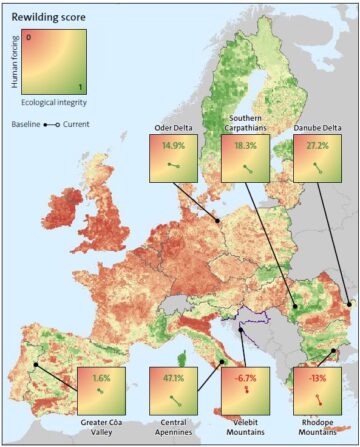

In 2020, this three-axis framework was used as the basis for evaluating rewilding impact across seven of Rewilding Europe’s operational areas. A total of 19 indicators (10 relating to human intervention and nine to ecological health – see Table 1 for more details) were selected to measure the ecological impact of rewilding interventions across each of the three framework components, plus an additional socio-ecological component. Baseline values for each of these indicators, which were set to the year that rewilding in each area began, were then compared with values as they stood in December 2020. Changes in these indicators were then used to generate an overall rewilding score for each area.

A scoring spectrum

As the Ecography paper reveals, the new approach to monitoring impact generated some interesting results (see Figure 2). Five of the eight rewilding areas saw an increase in rewilding score over time, while two areas saw decreases (the Rhodope Mountains and Velebit Mountains). The five areas where the score had increased all reported decreases in interventions by humans in the landscape, while four of these areas also reported increases in ecological health.

The biggest improvement over time was reported in the Central Apennines, with a relative increase of 47.1% from 2012 to 2020, and improvements in 14 of the 19 indicators. The Rhodope Mountains reported the largest decrease in rewilding score over time, with a change of -13% from 2011 to 2020.

Nuanced interpretation

It is important to note that a negative rewilding score for a landscape-scale rewilding area does not mean that rewilding interventions at specific, smaller scale sites within that area are failing to have a positive impact. Nature also moves to its own rhythms and timescales, which means such interventions may take decades to generate measurable impact.

“In applying the new methodology at landscape scale, we wanted to look at potential for upscaling rewilding,” explains Josiane Segar. “This bigger picture approach not only took into account the direct, site-specific interventions of Rewilding Europe’s operational area teams, but also changes happening outside pilot sites. Some or all of these changes may be outside the control of rewilding teams.”

The Rhodope Mountains rewilding area, for example, has been affected by a trend that has seen land abandonment beginning in the 1990s recently revert back towards agricultural intensification and encroachment as a result of Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) subsidies. This has manifested itself in the ploughing of high-biodiversity value grasslands and mosaics into arable fields, as well as an increase in livestock and grazing intensity, both of which have negative implications for rewilding progress. In order to counterbalance this threat, rural policies may need to be better targeted to allow people to make better use of the socio-economic benefits that rewilding can provide.

Strengths and weaknesses

The new study also compiled key success and threat factors for rewilding progress, based on an assessment by rewilding area teams (see Figure 3).

“This revealed that the major challenges to rewilding progress are related to policies that promote land-use intensification, such as CAP, and the persecution of keystone species,” says Segar. “Conversely, the most important factors aiding progress related to the appeal of rewilding as a concept and effective communications about rewilding results. Creating new economic opportunities and establishing good working relationships with stakeholders were also judged to be important.”

Moving forward

Today, interest in rewilding is growing rapidly – among scientists, policymakers, businesses and the public. Yet the application and upscaling of rewilding beyond pilot sites remains limited. This can be partly attributed to a lack of monitoring, with the long-term consequences of rewilding interactions still poorly understood.

“Until now there has been very little robust scientific assessment of whether rewilding actually works,” says Henrique Pereira, a researcher at MLU and iDiv and co-author of the new paper. “This new study, representing innovation at the intersection of rewilding science and practice, is therefore really important. I expect the methodology underpinning it to be picked up by many other researchers and rewilding practitioners, adapted and used. Beyond the numerical scores, this is a practical tool that can really help to inform decision making and drive rewilding onwards and upwards.”

Using the new methodology, rewilding impact will now be measured across Rewilding Europe’s rewilding areas every three to five years – this will allow sufficient time for ecological parameters to respond to rewilding interventions and ongoing area management. To complement and ease the task of expert-led assessment, Rewilding Europe’s monitoring team are currently developing data-driven, remote sensing approaches to monitoring, in partnership with The Nature Conservancy and several universities. This is particularly important in areas where ground-based measurements are likely to remain unfeasible due to resource restrictions.

Above all, the results of the new study show that the ability of rewilding to progress and scale-up is often constrained by pressures that are dictated by factors external to rewilding sites. As such, creating an environment more conducive to rewilding can often only come about through policy change at national and EU level.

“It’s clear that rewilding efforts are already beginning to have a positive impact at local scale,” says Josiane Segar. “However, future efforts should be better complemented by policy and advocacy if rewilding is to become scalable across entire landscapes.”