In the middle of June, a second group of cinereous vultures were translocated to the Rhodope Mountains rewilding landscape in Bulgaria. Their arrival and eventual release is the next step in a long-term programme to re-establish these ecologically important birds as a breeding species.

Raptor’s return

Following the groundbreaking release of 14 cinereous (black) vultures in the Rhodope Mountains of Bulgaria in November 2022, another group of 13 vultures arrived in the local rewilding landscape in the third week of June. The birds are being housed in a specially built adaptation aviary until the autumn, when they will be set free to join the birds released last year. The vultures are expected to form a colony together, as this keystone species gradually re-establishes itself within the local ecosystem.

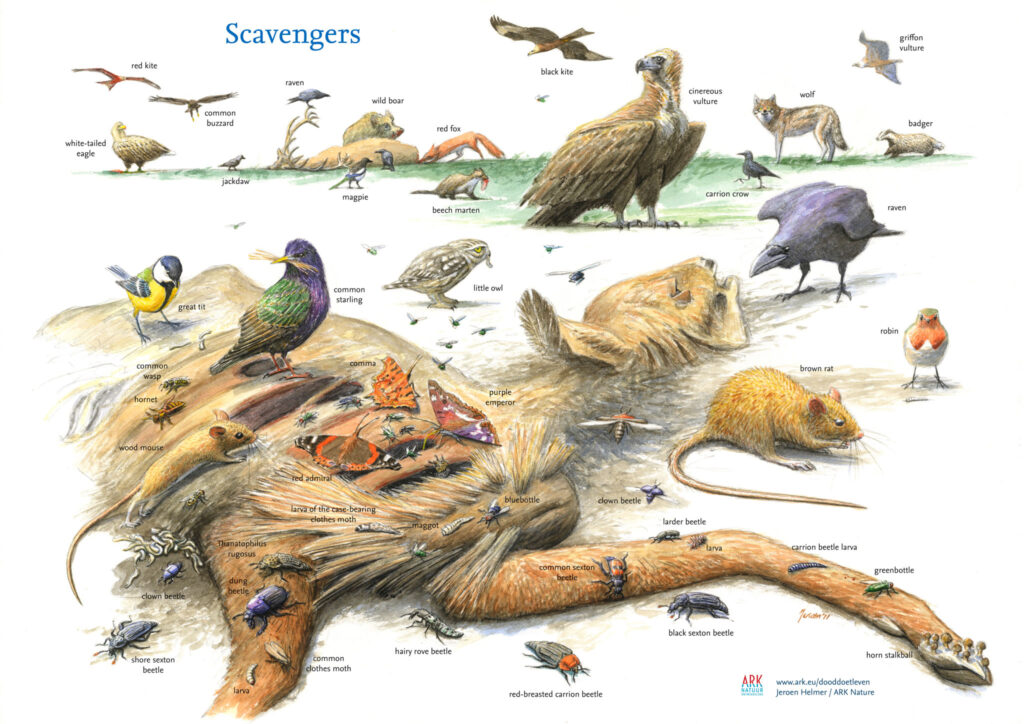

The cinereous vulture has been extinct as a breeding species in Bulgaria’s Eastern Rhodope Mountains since 1993 – it is hoped that the released birds will soon nest and raise offspring. As part of the rewilding vision for the local landscape, the return of Europe’s heaviest and largest raptor promises to restore a vital part of the circle of life. The restoration of food chains by the Rewilding Rhodopes team – which also involves the return of European bison, red and fallow deer and semi-wild horses – will enhance the health and resilience of the Rhodopean landscape. The presence of the vultures will also support the further development of nature-based tourism, delivering economic benefits to local communities.

The road to recovery

The cinereous vulture once lived across most of Europe, but numbers have declined dramatically over the last 200 years, largely as a result of poisoning and a decline in the availability of food. This has left fragmented populations clinging on, with 3,000 pairs in Spain, 35 pairs in France (reintroduced), 35 pairs in Greece, and 35 pairs in Portugal (natural recolonisation), as well as newly formed breeding colonies in Bulgaria’s Stara Planina (Balkan) Mountains. The reintroduction programme in the Eastern Rhodopes is another step forward in ensuring these iconic and ecologically important birds once again soar across the breadth of European skies.

Most of the cinereous vultures released in 2022 are doing well and have adjusted to life in the Eastern Rhodopes, although the loss of several birds highlights the outstanding challenges of raptor rewilding in the Balkans. The Rewilding Rhodopes team have constructed 13 artificial nests to encourage the birds to stay in the area and breed, and are gaining insight into the behaviour of the birds through GPS transmitters. The knowledge and expertise gained by the team should prove invaluable as the reintroduction programme continues.

The previously released birds have successfully socialised with the other two vulture species in the area (Egyptian and griffon vultures), and are feeding together and making longer journeys, both within Bulgaria and further afield.

Long-term programme

The cinereous vulture recovery programme in the Rhodope Mountains is being carried out by the Bulgarian Society for the Protection of Birds (BSPB), in cooperation with the Rewilding Rhodopes team, and is being funded by Rewilding Europe. The birds were provided by the Spanish NGO GREFA (Grupo de Rehabilitación de la Fauna Autóctona), which has been working for years to rescue and rehabilitate injured wild birds. It took almost three days to transport the vultures the 3,300 kilometres from Spain to the Rhodopes.

After their arrival the vultures were carefully transferred into individual shipping boxes and transported to the aviary. The birds are being closely monitored to ensure their adaptation is proceeding normally and that they remain in good condition.

The ongoing cinereous vulture reintroduction programme will see six to 10 birds released annually in the Eastern Rhodopes over the next few years. The establishment of a colony in the Eastern Rhodopes will support the survival of the species in the Balkans – an exchange of birds is expected with the last surviving breeding colony of about 25 to 30 pairs in Dadia National Park in Greece, and with the new colonies in the Stara Planina (Balkan) Mountains.