An essential process

Natural grazing by herbivorous animals is critical to the functionality and resilience of many European ecosystems. It can enhance biodiversity by opening up landscapes and preventing encroachment by shrubs, reduce the risk of catastrophic fire, and increase carbon storage and climate change resilience. Returning iconic grazers such as European bison and kulan (Asiatic ass) to the landscape can also support the growth of nature-based economies, generating jobs and a new pride in local nature.

This wide range of positive impacts is the reason why Rewilding Europe has worked so hard to boost natural grazing in Europe over the last decade, both within its own rewilding landscapes, and by supporting other European rewilding initiatives.

≈1500

grazing animals reintroduced to European landscapes by Rewilding Europe since 2011.

≈13,000

hectares under grazing by wild/semi-wild herbivores (Rewilding Europe landscapes and European Rewilding Network areas).

Boosting biodiversity

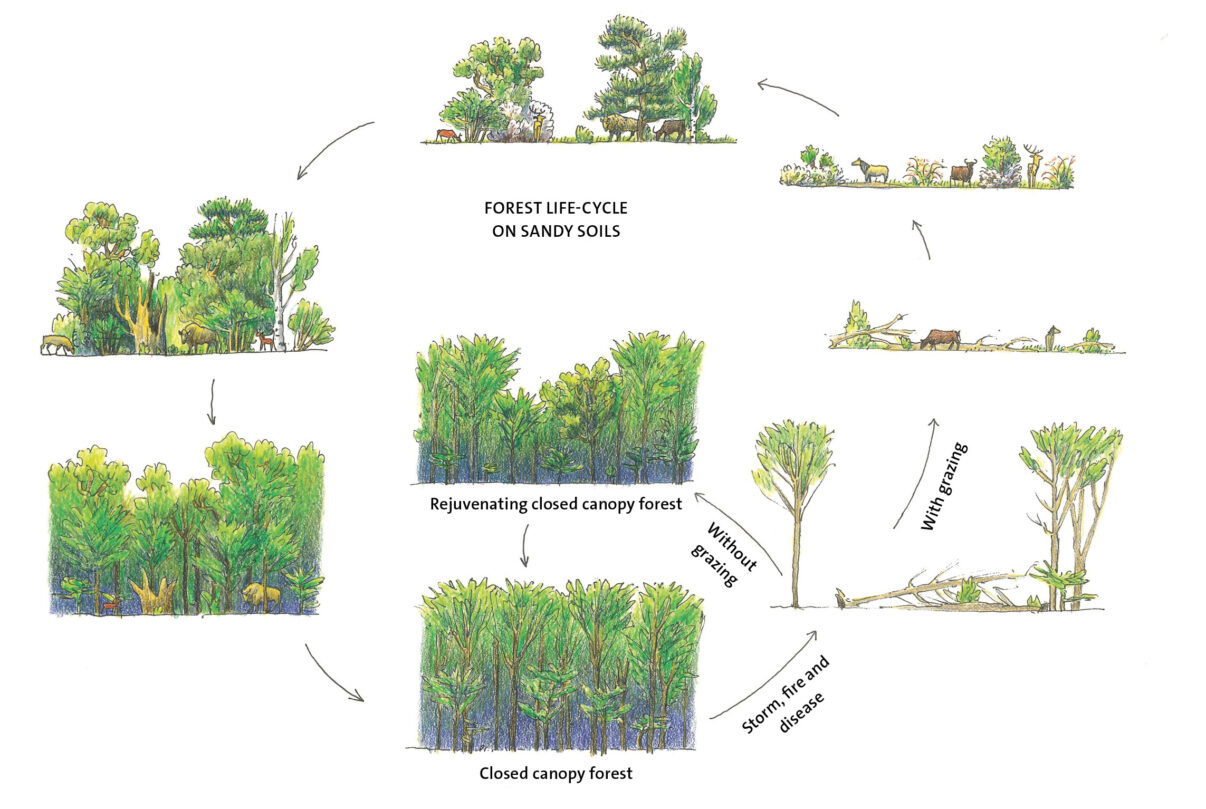

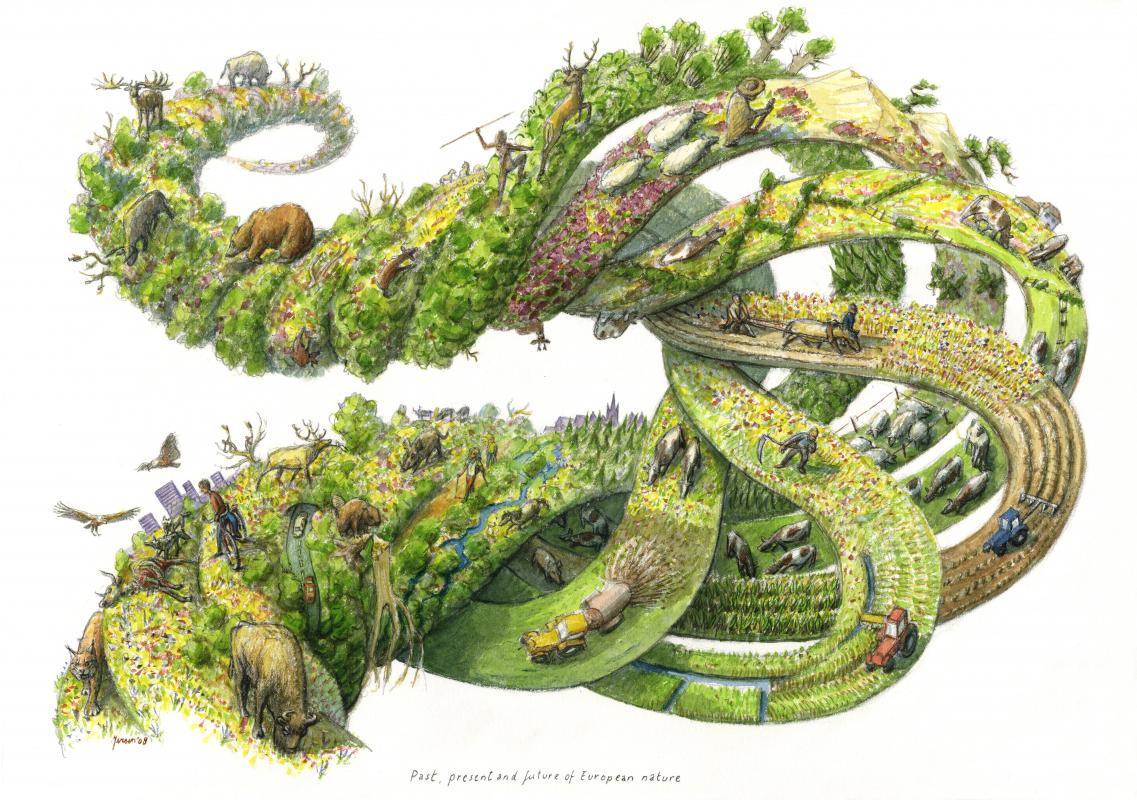

Before humans began to reshape Europe’s natural landscape, wild herbivores such as the European bison, elk, wild horse, auroch, beaver and various deer species were present in Europe in huge numbers. Their different grazing techniques and methods of physical disturbance – from trampling and wallowing to snapping branches and de-barking trees – together with their ability to transfer nutrients and disperse seeds over wide areas, created a dynamic, shifting landscape of woodland, open grown trees, scrubland, grassland, groves and thorny thickets. This mosaic habitat supported a hugely diverse range of wildlife species.

Factors such as domestication and changes in land use eventually saw most of Europe’s wild herbivores replaced by livestock. Today, with the ongoing trend of land abandonment and rural depopulation resulting in declining livestock numbers in many parts of Europe, there is a growing need and opportunity to return free-roaming wild herbivores (or their close equivalent) to European landscapes.

Since 2011, Rewilding Europe has been working to increase populations of wild and semi-wild herbivores in many of its rewilding landscapes. Such efforts have involved creating the conditions for such species to come back of their own accord, as well as direct reintroductions and restockings. As the populations of such herbivores increase, so their growing impact on the landscape is leading to the recreation of biodiversity-rich mosaic habitats.

On the ground

On Ermakov Island in the Ukrainian part of the Danube Delta rewilding landscape, for example, the local rewilding team have translocated water buffalo, Konik horses, red deer and fallow deer in recent years. All of these animals have acclimatised well to their new environment, with herds giving birth to offspring since their release.

Water buffalo, Konik horse and fallow deer releases in the Danube Delta

While the vegetation structure on Ermakov Island appears to have become slightly more varied since the release of these herbivores, the connection between the two needs to be verified with remote sensing. What has already been confirmed on the island is the beneficial impact of horses and water buffalo on the false indigo-bush (Amorpha fruticosa). Through their eating and trampling, the animals are helping to control this invasive species, which can prevent the natural regeneration of indigenous trees.

And in the Rhodope Mountains rewilding landscape in Bulgaria, the reintroduction of European bison, fallow and red deer, Konik horses and Karakachan horses is also leading to the creation of new mosaic landscapes.

“The Rhodope Mountains has a problem because people are leaving this area,” says Rewilding Europe co-founder Wouter Helmer. “That means the landscape is transforming from being half open and very diverse to one that is being encroached on by forest and shrubs. Bringing back wild herbivores tips the landscape back to one that is open again, which in turn benefits many species, such as the souslik (European ground squirrel) and tortoise.”

Increasing wild and semi-wild herbivore populations also helps to support carnivores and scavengers by increasing the availability of natural prey and carrion in the landscape. This is the case in the Rhodope Mountains, where the reintroduction of red and fallow deer is supporting local wolf and vulture populations. You can read more about this in our second impact story on the Circle of Life.

“Through their interaction with the landscape, big grazers and browsers play an essential part in maintaining the health and functionality of many European ecosystems.”

Sophie Monsarrat

Rewilding Manager

Reducing catastrophic fire risk

In many parts of the world, including Europe, socio-economic factors are leading to rural depopulation, large-scale land abandonment, and the diminishing influence of livestock on the landscape. With nomadic practice and pastoralism also on the decline, extensive swathes of land are gradually being encroached on by shrubs and bushes, while trees are also accumulating combustible vegetation. The disappearance of natural firebreaks, combined with the effect of climate change, means the risk and severity of catastrophic fires is increasing.

Growing sums of money are now being invested in firefighting capacity to counter this increasing threat. But experience from the Greater Côa Valley rewilding landscape in Portugal has shown that grazing by large, free-roaming herds of herbivores can be a cheaper and lower impact way of controlling catastrophic fires, while boosting local biodiversity at the same time. Such herds are rapidly gaining a reputation as highly effective “grazing fire brigades”.

A study, carried out as part of the Rewilding Europe-coordinated GrazeLIFE initiative (2019–2021), confirmed the beneficial impact of natural grazing in terms of catastrophic fire risk mitigation. The findings of the study were published in a paper in the Journal of Applied Ecology, with the research team also providing recommendations as to how European and global fire and agricultural policies could be revised to better support this approach.

The people perspective

The beneficial impact of natural grazing isn’t limited to other wildlife species. In many of Rewilding Europe’s rewilding landscapes, efforts to support the comeback of iconic wild and semi-wild herbivores is also having a positive effect on local communities.

In the Southern Carpathians rewilding landscape in Romania, for example, Rewilding Europe and WWF Romania have been reintroducing European bison since 2014. Herds of this iconic animal, which are now growing naturally, are attracting growing numbers of tourists and wildlife enthusiasts, supporting the development of a thriving nature-based economy and a growing number of jobs and livelihoods.

The reintroduced bison are also strengthening the connection between local communities and wild nature, with the animals quickly becoming an important part of local culture and a growing source of pride.

On the Lika Plains, which is part of the Velebit Mountains rewilding landscape in Croatia, the reintroduction of Tauros and wild horses by the local rewilding team is steadily boosting the wildlife watching appeal of the area. The Rewilding Velebit team are in the early days of developing nature-based tourism in the area and there are plans to establish a visitor and education centre.

And in the Greater Côa Valley rewilding landscape, the reintroduction of wild horses is also supporting the growth of a nature-based economy. The return to the landscape of primitive breeds such as the Sorraia and Garrano is not only a wildlife spectacle in itself, but reinforces the valley’s cultural heritage, with horses depicted in many of the area’s famous Prehistoric cave paintings.

With its wide range of benefits, natural grazing is increasingly being turned to by European landowners as a far more sustainable and ecologically friendly alternative to intensive livestock farming. One of the most famous examples of a landholding that has made this transition is the Knepp Castle Estate in the UK. This former arable and dairy farm is now a world-famous rewilding initiative and member of Rewilding Europe’s European Rewilding Network.

The land at Knepp – which was once intensively farmed – has been devoted exclusively to rewilding since 2001, with a focus on the restoration of dynamic natural processes. The estate, which uses herds of grazers such as Old English longhorn cattle, Exmoor ponies and Tamworth pigs, as well as red and fallow deer, to drive mosaic habitat generation, has already seen extraordinary increases in wildlife, including some of the rarest birds and insects in the UK.

Bending the climate change curve

The impact of terrestrial and marine wildlife populations (both herbivores and carnivores) on the carbon cycle is complex. Nevertheless, scientific research has already proven that there is huge potential to scale up climate change mitigation by restoring such populations to significant, near historic levels. This science is called “animating the carbon cycle”.

Results from the GrazeLIFE initiative confirmed that mosaic landscapes, complete with naturally occurring populations of free-roaming herbivores, can help to significantly reduce the scale and impact of climate change. Whereas grasslands are sometimes more effective at long-term carbon sequestration than forests, natural forest mosaics (particularly old-growth forests) have large carbon storage capacities. An added benefit of mosaic landscapes is that they help species of both closed and open vegetation types adapt to climate change. Because they are far more “permeable” than landscapes with hard boundaries, they allow such species to move northward as climate zones shift.

The connection between rewilding and climate change will be explored in more detail in the next impact story (the fifth in the series).

Natural Grazing Facility

Webinars covering natural grazing are regularly organised by the European Rewilding Network (ERN), for example, many of whose members oversee initiatives involving wild or semi-wild herbivores. ERN members also have access to the Natural Grazing Facility, which supports the widespread adoption of natural grazing practices throughout Europe by connecting demand and supply of herbivores among organisations dedicated to rewilding principles.

Those looking to reintroduce natural grazers into landscapes as part of rewilding initiatives invariably have many questions about the practicalities of the reintroduction, and its potential impact on the landscape. Many of these questions, including which herbivore species to use, which breeds, and in what numbers, are addressed in Rewilding Europe’s dedicated natural grazing booklet.

Those looking to reintroduce natural grazers into landscapes as part of rewilding initiatives invariably have many questions about the practicalities of the reintroduction, and its potential impact on the landscape. Many of these questions, including which herbivore species to use, which breeds, and in what numbers, are addressed in Rewilding Europe’s dedicated natural grazing booklet.Tauros collaboration

As the ancestor of all domesticated cattle, it is hard to think of a more important animal in the history of mankind than the auroch. Once widespread across Europe, it was a keystone species within many continental ecosystems. But by 1627 this impressive animal had been hunted to extinction throughout its range.

The auroch may be long gone, yet all is not lost. Today, strands of its DNA remain alive, distributed among a number of ancient cattle breeds that still exist across Europe. Using these breeds, Rewilding Europe began collaborating with the Dutch Taurus Foundation in 2013 to bring aurochs back to life. This is the Tauros programme.

The aim of the Tauros programme is to bring back a functional version of the auroch – called the Tauros – by establishing viable wild populations of this impressive animal in several European locations. This, in turn, will boost the role of the Tauros as a natural grazer and benefit biodiversity through the creation of biodiversity-rich mosaic landscapes across the continent. A resilient animal, the Tauros is well-adapted to living in the wild, with herds capable of defending themselves against predation.

“There have been challenges, of course, but I would say that the development of the programme has been a success,” says Ronald Goderie, Director of the Taurus Foundation. “The numbers of Tauros have grown and we have exported herds to new rewilding areas outside of the Netherlands. On the Lika Plains, in the Velebit rewilding landscape, for example, you can really start to see the benefits that a wild herd of Tauros could deliver, with the vegetation gradually becoming more open.”

A sprawling, high altitude grassland, ringed by the craggy limestone peaks of the Velebit Mountains, the Lika Plains officially opened as a natural grazing pilot in 2015. A succession of releases mean there are now more than 100 Tauros roaming the grazing area, which recently expanded from 800 to 1500 hectares, together with around 100 native horses (Koniks and Bosnian mountain horses). These animals are already starting to have an impact on the landscape.

“On the Lika Plains, in the Velebit rewilding landscape, you can really start to see the benefits that a wild herd of Tauros could deliver, with the vegetation gradually becoming more open.”

Ronald Goderie

Director of the Taurus Foundation

Policy progress

Coordinated by Rewilding Europe, the GrazeLIFE initiative ran from 2019 to 2021. Funded by the European Commission, its aim was to evaluate the benefits of various land management models involving domesticated and wild/semi-wild herbivores, enabling the most effective models to be better supported by EU policies and legislation. Research carried out as part of the initiative confirmed the value of wild and semi-wild herbivores in creating and maintaining high-biodiversity mosaic landscapes.

The results and multiple recommendations generated by GrazeLIFE were presented in a layman’s report, published at the end of 2021. A practitioners’ guide was also published, to support the adoption of the most effective natural grazing practices across Europe. These publications were complemented by an online symposium, attended by 335 participants from 38 countries, which saw a range of keynote speakers present the outcomes of the initiative and provide a detailed overview of the benefits that natural grazing can provide. The GrazeLIFE consortium also produced a report on how European policies – particularly the Common Agricultural Policy – can better support extensive (natural) grazing.

Lessons learned

Horses, bovines, wild boar, deer and ibex are all social animals. We have a very clear view of how the social structures of deer and boar work as we have studied these animals in the wild for a long time. But due to domestication, we have lost our view of how herds of horses and bovines are naturally structured. Most of what we know today comes from farm-managed animals.

As the bison reintroduction programme in the Southern Carpathians progressed the local rewilding team learned the importance of allowing bison from different zoos and reservations to form social, non-habituated groups prior to their release. This gave the animals the greatest chance of thriving in the wild.

Another valuable lesson learned during efforts to enhance natural grazing was the importance of improving European grazing-related policy.

“In the first five or six years after Rewilding Europe was founded we faced incredible barriers at the policy level when it came to natural grazing,” says Raquel Filgueiras, Rewilding Europe’s Lead Impact Monitoring & Research. “This is why the GrazeLIFE initiative was so necessary, and the reason why the GrazeLIFE team put forward 50-plus recommendations to the European Commission.

“A lot of work still needs to be done in this area, because the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) still needs major changes to make it more supportive of natural grazing. If low-intensity natural grazing with livestock was competitive with the industrial-scale production of livestock by 2030, this would provide a massive boost.”

“If low-intensity natural grazing with livestock was competitive with the industrial-scale production of livestock by 2030, this would provide a massive boost.”

Raquel Filgueiras

Rewilding Europe’s Lead Impact Monitoring & Research

Future focus

Natural grazing is a cornerstone ecological process, delivering a wide range of benefits for European nature and people. As such, Rewilding Europe is committed to scaling up natural grazing across Europe over the next decade. This is part of our renewed commitment to creating wilder nature, which is outlined in our new Strategic Plan 2021–2030.

Over the next 10 years, Rewilding Europe will expand the number of rewilding landscapes in which it showcases practical rewilding from 10 to 15. In the majority of these landscapes rewilding efforts will focus on enhancing natural grazing – through further releases of wild and semi-wild herbivores, and by supporting existing herbivore populations and wildlife comeback. The southern end of the Iberian Chain, for example, which is located in central eastern Spain, has huge scope to increase natural grazing with wild horses and other grazers. In 2019, Rewilding Europe received a grant from the Endangered Landscapes Programme to explore the rewilding potential of the area.

“By 2030 I would like to see a much larger number of wild and semi-wild grazers across all of Rewilding Europe’s rewilding landscapes, and for a mix of herbivore species – bison, horses, deer, Tauros – to be present,” says Raquel Filgueiras. “Then we will really start to see the beneficial ecological impact of natural grazing take off.”