From European bison in the Southern Carpathians and red deer in the Rhodope Mountains to Konik horses in the Danube Delta and Tauros in the Velebit Mountains, Rewilding Europe is reintroducing wildlife species in many of its operational areas. These reintroductions are carried out after careful evaluation and always follow established scientific guidelines. Deli Saavedra, Rewilding Europe’s Rewilding Area Coordinator, has been involved with many reintroduction programmes. He explains more.

A lot of wildlife species – such as wolves and bears – are making a comeback of their own accord in Europe. Why do we still need to reintroduce some species?

It is true that some animals are making a comeback in Europe on their own, especially when we create the right conditions for them to do so. But in some cases the nearest populations of our target species are too far away to return in a reasonable period of time, or there are barriers such as roads or dams that make a return impossible. In other cases, the species is already in the area but in small numbers; we can boost these numbers by bringing in more animals, which not only increases population density but can also improve genetic composition. We call this process restocking, rather than reintroduction.

Before a decision is taken on whether or not to carry out a reintroduction, what kind of factors need to be considered?

There are many factors to be considered before embarking on a reintroduction – an action that typically requires a considerable investment of time and resources. All these factors are assessed in a feasibility study.

Feasibility studies are key to assessing whether a reintroduction can go ahead, as well as its eventual outcome. The questions we typically ask ourselves are mainly common sense: what caused the animal to disappear in the first place? Could those causes still have an impact on reintroduced animals now? If this is the case, there is no point in carrying out the reintroduction until these causes are removed. Another thing to consider is whether the source population will be damaged by removing individuals for the reintroduction.

The feasibility study is also used to assess the degree of social acceptance in the proposed release area – which is critical to any reintroduction. The IUCN has developed specific guidelines for reintroductions, which Rewilding Europe always follows.

What is the overall objective of a typical reintroduction?

For Rewilding Europe, the main objective of species reintroductions is to recover wild nature. By bringing back missing parts of ecosystems, we make them more complete and resilient, which means they can do a better job of managing themselves.

Reintroductions are sometimes critical to preventing species extinction; by creating new populations, we can move away from situations where animals are concentrated in one particular area and therefore overexposed to threats that could cause extinction. An example of this is Rewilding Europe’s work to establish a new breeding colony of cinereous (black) vultures in the Rhodope Mountains of Bulgaria, with only one colony of these birds currently existing in the Balkan region.

How do we decide when the population of a species being reintroduced in a particular location has reached minimum viability?

Scientists have proposed different thresholds for determining when new populations are viable. With some species, for example, 50 individuals are considered to be enough to sustain a viable population. In other cases, the threshold is considered to have been passed when a first generation of individuals has been born in the release area and has then bred successfully. There are also mathematical models that can be used. Regardless of how viability is determined, it is always important to monitor the reintroduced animals closely in the first few years after their release – this gives a clearer picture as to the degree of population viability.

Are some species more suitable for reintroduction than others? Can you give some examples?

Many species can be reintroduced. Not only large animals, but amphibians, fish, insects, plants and even mushrooms. The latest report of the Reintroduction Specialist Group of the IUCN details reintroductions involving everything from blister beetles in Sweden and Asian elephants in Sri Lanka to summer snowflakes in Italy and Amazonian manatees in Brazil.

Is it more important to reintroduce keystone species? What about single species versus groups of species?

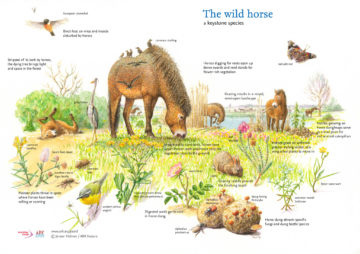

Rewilding practitioners typically concentrate their efforts on the reintroduction of keystone species, because these are the ones which will have the most impact in terms of ecosystem restoration. Large herbivores maintain open areas that benefit a wide range of other species through their grazing, scavengers act as nature’s “clean-up crew”, and animals such as rabbits, sousliks and roe deer are the main prey for a wide range of European carnivores. If possible, it is sometimes better to restore groups of species. An example would be different herbivores (such as deer, horses and bison), as each species impacts the landscape in a different way.

Are there important rules or guidelines for transporting wildlife species in Europe?

There many rules for transporting both wildlife and livestock (when we translocate horses or Tauros, even if they will eventually live in wild or semi-wild conditions they are still legally considered livestock).

Some of the toughest challenges for reintroductions can arise from the extensive regulations governing transports. The huge differences between countries in terms of regulations often makes international transportation even more challenging. To transport horses from Latvia to Ukraine, for example, we have to test the animals for almost 20 different diseases. The list of tests is different in each country, so if you prepare the same transport to Croatia, the list changes. And these lists are regularly updated, just to make things even more complicated.

When Rewilding Europe carries out a reintroduction, where do the animals come from?

Usually, the animals come from abundant populations of the selected species elsewhere. Most of our reintroductions are based on translocations (moving individuals from the donor population to the reintroduction site), but we also use individuals bred in captivity in zoos or breeding centres, like some of the European bison released in the Southern Carpathians and the kulan (wild ass) brought to the Danube Delta.

After a species has been reintroduced, what measures can be taken to maximise the success of that reintroduction?

Intensive monitoring is essential, using methods such as radio-tracking or camera trapping. It is especially important to know when the released animals begin to reproduce, or if they die, what the causes of mortality are. Reintroduced animals can die due to unforeseen causes; in this case, we should react quickly, maybe changing protocols, with specific surveillance, or even stopping the reintroduction until we understand how to overcome the threat. This is called adaptive management: any reintroduction project should be flexible and committed to finding solutions to unforeseen problems that arise.