On April 24 this year, one of the first members of the European Rewilding Network – the European Bison Project in Kraansvlak – celebrated its 10 year anniversary. In this blog, European Rewilding Network Exchange Officer and bison project coordinator Yvonne Kemp shares an inspirational story about the developing relationship between European bison and the people of the Netherlands.

It has been a real thrill for me to encounter the herd of European bison roaming the Kraansvlak (an area of coastal dunes in the Netherlands) several times recently. On each occasion I have felt proud and privileged to be able to present Europe’s largest living land mammal to nature lovers from across the globe. One such visitor remarked at my obvious delight at seeing these magnificent beasts. Although I have seen these bison many times, their presence still fills me with awe and wonder.

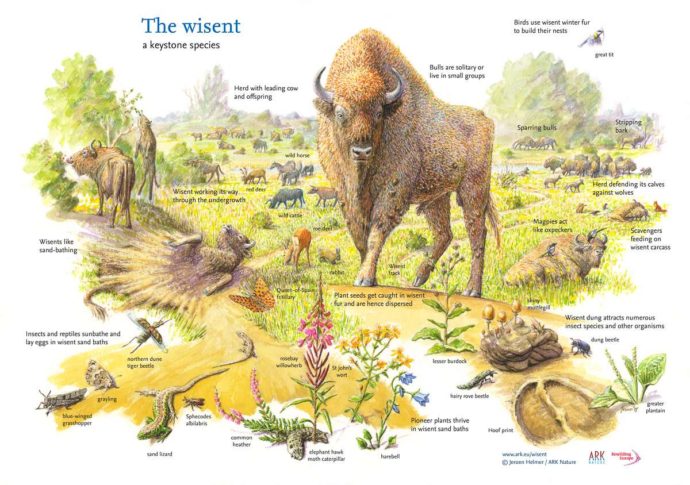

When thinking of bison, the image that springs to mind for most people is of vast herds of these furry giants crossing the pancake-flat plains of North America. An incredibly impressive sight, without doubt. But many are unaware that the American bison has a relative which happens to live in Europe: the European bison, or wisent.

Ask a Polish person about bison and you’re pretty sure to get a positive response. After all, Poland was one of the countries were wild European bison survived the longest – until around a century ago. It is also the place where a special breeding programme allowed them to be reintroduced into the wild, in the 1950s.

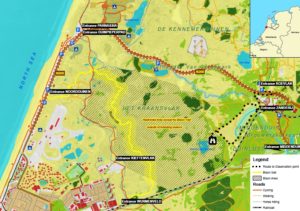

At the turn of the twenty-first century, a handful of Dutch people aware of European bison would have associated these animals with the forests of Poland. Fast forward to today and many residents of the Netherlands now know this special animal. Not specifically because of the Polish vodka branded with bison images, but because European bison were released into a Dutch nature reserve called Kraansvlak, part of the Zuid-Kennemerland National Park, in April 2007.

I wasn’t there on this special day. To be honest, I wasn’t even aware of the release project until I searched for an inspiring internship for an ecologist-in-the-making back in 2010. Since then, however, my connection with bison has deepened considerably.

I am now writing these words ten years after the very first steps of bison in Dutch nature, in honour of those who were brave enough to attempt such a feat. Bison roaming in coastal dunes? Those crazy Dutch. In those days, the European bison was considered the king of the forest. What good could possibly come from removing this majestic animal from its green kingdom?

The European bison is considered an endangered animal. It is listed as “vulnerable” on the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This is hardly surprising, considering the species became extinct in the wild in the 1920s, only surviving thanks to the perseverance of several bison conservationists who managed to release a number of animals back into the Polish wild 30 years later. Every European bison alive today dates back to just 12 animals.

It was in 1932 that a register of all living bison was compiled for the very first time. We have known it ever since as the European Bison Pedigree Book, published once a year, every year. It contains updated information on bison living in all kinds of locations, both roaming free and in captivity.

According to the book, the European bison population totalled less than 2,800 individuals at the turn of the millennium. Slightly over half in the wild, with the remainder living in parks and zoos. Less than 2,800! Only a teenage life ago! With only a handful of areas boasting populations totalling over 100 animals.

Since the dark days of its near extinction, the European bison has made a remarkable comeback. In 2004, the IUCN’s Species Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan called for the continuation of captive bison breeding and reintroduction projects. More and bigger areas with bison, where the animals could multiply. And the need for research in different types of habitat, to increase our understanding of bison living outside highly forested areas. Those few Dutch people had their pioneering idea at the perfect moment!

In 2007-2008 six bison were brought all the way from Poland to a new home close to the Dutch coast. Kraansvlak is a half open dune landscape, where fallow and roe deer roam in silence, and rabbits check their backs for the stealthy red fox. Bush grass waves in the salty sea breeze, vast areas of crested hair-grass give way to the white flowered burnet rose, and sandy dune tops alternate with scrub-rich valleys that support species such as sea buckthorn, laden with ochre fruit. Every season has something to offer here, from highly scented white hawthorn flowers in spring, to acorn carpets in autumn.

This kind of half open scenery turns out to be an ideal bison retreat. With minimal human intervention, the animals roam here all year round without supplemental food (in contrast to most European bison places). It affords the unique opportunity to study these magnificent herbivores while they eat and rest.

And European bison definitely rest. Digestive reasons play a significant role, but having studied them as an intern in winter, with fingers on the edge of frostbite, I get the impression that they like to take it easy. Having studied their foraging behaviour, we have learned that European bison much prefer to debark spindle tree shrubs, with the resultant dead stands then giving way to grasses. Also, the bison like to spend many hours in the rough grassy areas. Combining data it all makes sense; some seventy percent of their diet consists of grasses, year round, complemented with woody bites.

With over ten years of study conducted on Kraansvlak bison biology, involving over 50 students, a significant quantity of data has now been collected. Perhaps the most interesting revelation has been bison behaviour – more specifically, their relationship with humans, and vice versa. As bison are gaining an increasingly firm footing in the Netherlands, it takes people to realise that this animal is a very different beast to the cattle roaming around in many Dutch nature areas.

The Kraansvlak project has taken human-bison interaction very seriously. After a few months of habituation, the first excursions in the reserve were organised. Since then, these regular planned excursions have been fully booked, and we have now added dedicated photographic tours and horseback safaris.

An area of 330 hectares may seem small, but the conditions in Kraansvlak give visitors an authentic natural experience, despite the reserve’s proximity to coast and city. Since 2012 a half yearly hiking trail has been open to the public, with over 15,000 visits have being paid using this natural walkway. With the chances of witnessing a semi-wild herd of bison in the reserve good to great, guidelines instruct people how to behave should they encounter animals on their visit. And as they come to understand more about the bison, people become accustomed to acting in the right way when they meet them.

Witnessing a group of 20 bison going straight through spiny sea buckthorn with their thick skin, opening the door for other animals. Or spending an hour watching a tightly knit group ruminating on a sandy spot, their coats burnished gold by the afternoon sun. It’s magic. Looking in detail you come to appreciate their social hierarchy, their skilful way of jumping up to reach the tastiest leaves, their wallowing action – full of spirit.

So far over 25 bison have been born within the Kraansvlak project, and we have had the privilege to send bison to new projects. Their social integration is remarkable. Last summer two bulls were brought to the area and within 24 hours they had blended in with the herd, as well as their new environment. The result so far: six calves frolicking in the reserve.

Knowing that the Kraansvlak project contributes to overall bison conservation makes me proud, especially of the people who have made this possible in the first place. They were thinking outside the established box, and started this adventure well prepared and with plenty of enthusiasm. To date, everyone involved has been learning and enthusiastically sharing their insight and experiences. A novel idea, maybe a dreamy wish, can really make a difference – either way it’s a wonderful way of contributing to the conservation of an endangered species and adding value to nature, while trying your best to involve people. The bottom line is: if we can make such a project a success in the tiny, crowded country of the Netherlands, then we should definitely be able to boost bison numbers in more areas where it historically once roamed.

Later this year we will celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Kraansvlak bison project with public activities and a conference. We feel that it is vital to share and demonstrate what we have experienced so far, in the hope it will open people’s minds to the fantastic opportunities for bison conservation. We are therefore delighted to have been one of the very first members of the European Rewilding Network, not only sharing our knowledge, but also learning from other like-minded people and becoming inspired by rewilding projects from across Europe.

Later this year we will celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Kraansvlak bison project with public activities and a conference. We feel that it is vital to share and demonstrate what we have experienced so far, in the hope it will open people’s minds to the fantastic opportunities for bison conservation. We are therefore delighted to have been one of the very first members of the European Rewilding Network, not only sharing our knowledge, but also learning from other like-minded people and becoming inspired by rewilding projects from across Europe.

From a personal point of view, it is amazing to be part of a society that is increasingly familiar with bison. This era has seen a doubling of European bison numbers since 2000, with two thirds of the 6,000-strong current bison population now roaming free in European nature. We are not there yet, but it is tremendously stimulating to see what dedication and determination can bring about. Let’s continue our work to bring more space for more bison. Let’s continue our mission to bring these majestic creatures back to European nature.

To find out more about the Kraansvlak bison project, please view this page.