With the help of Rewilding Portugal, the first landowner in Portugal’s Greater Côa Valley was recently granted a license to leave livestock carcasses in the field. This milestone moment for vulture conservation will hopefully lead to the award of many more licenses, amplifying the benefits for these iconic scavengers, local farmers, and society.

A groundbreaking moment

On a rocky hilltop on his 80-hectare farm, in the south of the Greater Côa Valley rewilding landscape near the Serra da Malcata in Portugal, Albano Alavedra leaves the bodies of two recently deceased goats. He then retreats to watch the inevitable spectacle. Before long, a group of griffon vultures gathers in the sky overhead. Singly and in pairs they begin to descend, the primary feathers on their huge wings clawing the air. Soon a small mass of birds has congregated on the dusty ground, squabbling over the carcasses. In time, nothing will be left but a few scattered bones.

This gathering of vultures is not only a captivating display of scavenging, but a milestone moment for vulture comeback in the local landscape. After a five-year-long wait, and with the ongoing support of the Rewilding Portugal team, Albano has finally obtained a license from the government to leave livestock carcasses in the field for free. From January this year, rather than being obliged to remove the bodies of dead goats from his farm – which takes time and money – he can let vultures do the job for him.

Good for vultures….

Albano’s carcass deposition site will not only benefit griffon vultures, which are thriving in the Greater Côa Valley, but also cinereous vultures, which are far rarer. His goat farm, which is home to around 300 goats, is located close to a colony of the birds, which was discovered by the Rewilding Portugal in the Malcata Natural Reserve in 2021. With 18 pairs, this is the third largest colony in the whole of Portugal.

“Carcass deposition sites are actually better for cinereous vultures than typical artificial feeding stations set up by conservation initiatives,” explains Rewilding Portugal’s rewilding officer Pedro Ribeiro. “At such stations you get a lot of carcasses put out on a regular basis, so they can attract huge groups of griffon vultures, which are very aggressive. It often results in a crazy feeding frenzy, which puts off cinereous vultures. In the case of farms like Albano’s, which might put out one or two carcasses a month, you get fewer griffon vultures, and the cinereous vultures are far more inclined to come in and feed. I’ve seen both griffon and cinereous vultures at his deposition site, as well as ravens, crows, and red and black kites.”

…. and good for people too

Portuguese livestock owners without carcass deposition licenses are legally obliged to pay for carcasses to be removed. However, in practice many simply leave them in the field anyway, because government-subsidised carcass removal services don’t typically extend to remote areas. In such areas, farmers are supposed to dig holes and bury their carcasses, but the ground is often too rocky to perform such a task.

“Because leaving carcasses in the wild is technically illegal without a license, people leave them where they’re hard to find,” says Pedro Ribeiro. “And because they’re hard to find for people, they’re also hard to find for vultures – under trees in a forest, for example.

“The same sites are used over and over again, like a landfill, so you have dozens of sheep, cows, and other animals rotting away without vultures disposing of them. This is bad for the environment, because you have wild boar, foxes, and dogs eating the carcasses, and then people come in and leave poisoned baits because they don’t like foxes. Legalising deposition sites, which are deliberately located in places where vultures can easily find them, is a win-win-win for farmers, vultures, and society in general. It could also benefit the Portuguese government, as they spend over a million euros a month subsidising carcass removal.”

Navigating bureaucracy

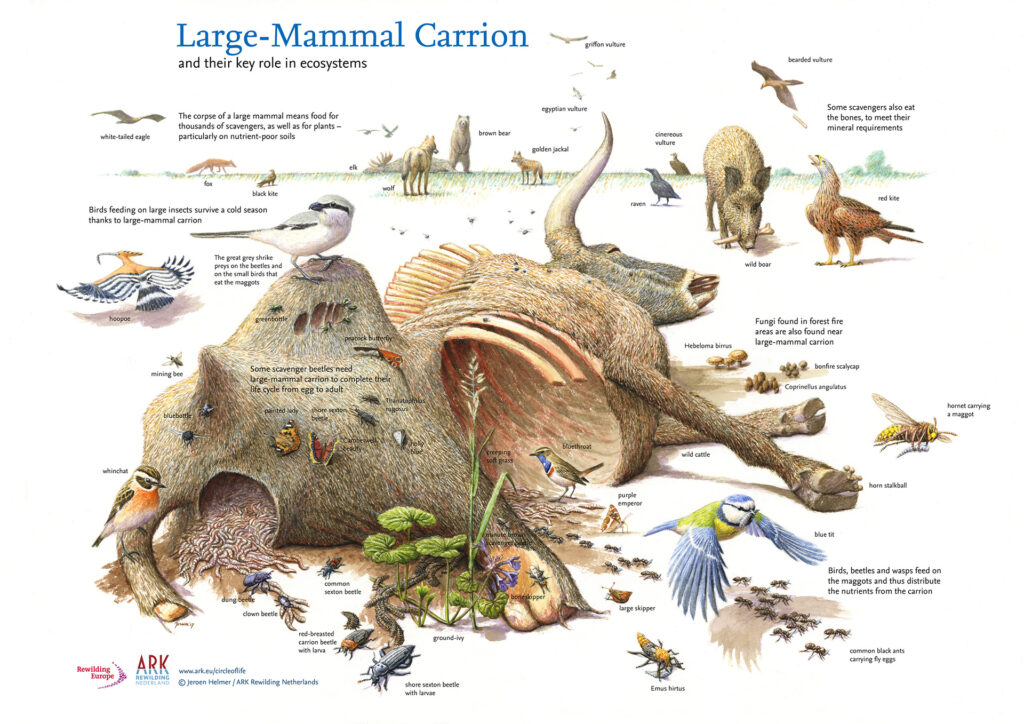

In an ideal world, vultures across Europe would feed exclusively on the carcasses of wild animals. This is one of the reasons why Rewilding Europe is working to strengthen the so-called “circle of life” in many of its landscapes by enhancing populations of free-roaming wild herbivores – such as European bison, wild horses, and deer. Yet the unnaturally low density of current wildlife populations in many places means livestock carcasses are often a critical source of food. This is the case in the Greater Côa Valley rewilding landscape, where extensively grazed livestock such as cattle and goats far outnumber wild herbivores such as deer.

Yet politics and agriculture have complicated this process. In the wake of the mad cow disease crisis in the early 2000s, the European Union imposed strict regulations banning the leaving of dead livestock in the field. Instead, the carcasses of domestic animals had to be collected from farms and destroyed. This drastically reduced the availability of food for scavenging birds such as vultures, negatively impacting their populations. While the EU later relaxed these restrictions, allowing carcasses to once again be left in nature, implementation has varied widely between countries. Some, like Spain, acted quickly to facilitate vulture feeding, while others – including Portugal – have been slower to act.

“In 2019, Portugal transcribed the change in European law into national law, which in theory meant farmers could once again leave carcasses in the field,” explains Pedro Ribeiro. “However, the process of applying for a carcass deposition license in this country is incredibly complex, bureaucratic, and time-consuming. At the moment we’re helping 10 extensive farmers in the landscape to apply for licenses and Albano is the first recipient.”

Towards a brighter future

Albano Alavedra is the first landowner in central Portugal to be granted a carcass deposition license. To date, only six licenses have been granted in the entire country.

“Obtaining this first license has been a challenge,” says Pedro Ribeiro. “But now we have it, hopefully it will be a breath of fresh air and the license approval process will accelerate. I’d love to see a reduction in the bureaucracy, so that farmers across Portugal can easily apply for licenses without needing help from an NGO. I have my fingers crossed that everything becomes more streamlined, because the benefits of free carcass deposition for vultures and farmers are clear and compelling.”

The granting of a license in the Greater Côa Valley is not just a milestone moment for the local landscape. It has the potential to set a precedent for vulture conservation across Europe. Countries such as Spain, where carcass deposition is already far more common, have already witnessed significant vulture population recoveries. By encouraging wider adoption across other European landscapes, policymakers now have the opportunity to restore a vital ecological process that has been disrupted for decades. A Europe where the carcasses of extensively farmed livestock support thriving vulture populations is within reach – the recent breakthrough in the Greater Côa Valley is a small but critical step towards making this vision a reality, on the path towards making the carcasses of wild herbivores more readily available.

Invaluable support

Rewilding Europe’s work in our rewilding landscapes is supported by a wide range of highly valued partners. We would particularly like to acknowledge those providing core funding – notably the Ecological Restoration Fund, the Dutch Postcode Lottery, WWF-Netherlands, and Arcadia. Their longstanding support plays a critical role in enabling us to deliver and scale up rewilding impact.