Rewilding Europe is working to accelerate the restoration of nature at landscape scale. Europe’s protected areas could play a pivotal role in the process.

The restoration imperative

From individual trees to sweeping sites covering hundreds of thousands of square kilometres, Europe’s protected areas are vital to nature conservation. With more than 100,000 distributed across 54 countries, Europe has more of such areas than any other region in the world. They include national parks, natural parks, nature reserves and protected landscapes – all of which are designated by individual countries – as well as the 27,000-plus areas of the Natura 2000 network, which the European Union (EU) established in 1992.

Yet while these numbers may seem impressive, simply protecting the nature we have left in Europe is not enough. It’s not enough to halt and reverse biodiversity decline, and it’s not enough to slow and stop climate change. In their current condition, the majority of Europe’s protected areas are part of degraded landscapes that are unable to support thriving wildlife populations, complex food webs or fully functioning ecosystems. And this means they are unable to provide the benefits upon which Europeans rely, such as clean air, fresh water, and the locking up of atmospheric carbon.

“This is why we urgently need to recover European nature and natural processes right across Europe,” says Frans Schepers, Managing Director of Rewilding Europe. “Rewilding, which is cost-effective, proven to work and available now, is the best way to achieve this, both inside and outside of protected areas. Wilder national parks would make a great foundation on which to scale up European-wide nature recovery.”

Moving up the scale

The need to make parks in Europe wilder was addressed by Schepers at the EUROPARC Conference 2021, which was held online in early October with the title “Parks in the Spotlight”. As a keynote speaker, he took a poll among the 150 participating EUROPARC members, with those most active in park management asked to rank their protected area in terms of wildness. On a scale of 1 to 10 (10 being fully wild), it was interesting to note that most awarded their area a score of 7 or 6, and many even lower.

The need to make parks in Europe wilder was addressed by Schepers at the EUROPARC Conference 2021, which was held online in early October with the title “Parks in the Spotlight”. As a keynote speaker, he took a poll among the 150 participating EUROPARC members, with those most active in park management asked to rank their protected area in terms of wildness. On a scale of 1 to 10 (10 being fully wild), it was interesting to note that most awarded their area a score of 7 or 6, and many even lower.

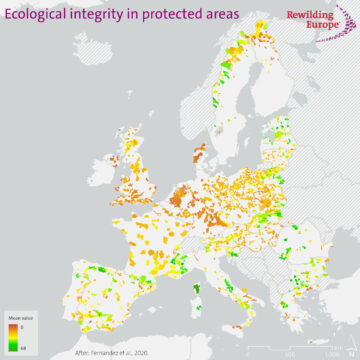

Schepers then presented a quick overview of the wildness of protected areas in Europe, based on a ranking of ecological integrity (essentially the ecological health of an area). This focused on all sites within EU Member States greater than 1000 hectares falling within IUCN I-VI protected area categories – this equates to more than 29,000 sites covering over 620,000 km2.

This preliminary analysis showed the majority of protected areas have very low ecological integrity (see map). While Category Ib (Wilderness Areas) and Category II (National Parks), which enjoy the highest levels of protection, typically have higher levels, they represent less than 4% (just over 1000 sites) of the areas included in the analysis, with a surface area of 128,575 km2 (just over 20% of the total area).

“This quick scan really brings home the huge potential to upgrade wildness in protected areas right across the EU,” says Rewilding Europe’s Managing Director.

Letting nature lead

From politicians and entrepreneurs to scientists and everyday citizens, interest in rewilding is now at an all-time high, with an ever-growing number of initiatives generating positive impact across Europe. This is stimulating a rethink about conservation and our relationship with wild nature.

Since it was founded in 2011, Rewilding Europe has pioneered this evolution, with its action-oriented, “showing by doing” philosophy resulting in a pan-European network of high-profile operational areas, complemented by the ever growing European Rewilding Network.

A set of rewilding principles has also been established, helping to define what is different and special about rewilding, providing coherence, inspiration and transparency, and positioning rewilding in relation to other conservation approaches.

Michael Hošek is President of the EUROPARC Federation, an independent, non-governmental organisation which works with national parks across Europe to enhance protection. He believes rewilding based on such principles can help to take Europe’s national parks and protected areas to the next level of wildness.

“Looking at Europe’s national parks and protected areas it is clear that some are far wilder than others. But in general we need to make more space for natural processes to reshape landscapes, rather than expending precious and often dwindling resources trying to reach and maintain artificial end points. Going forwards, there will still be a need for intervention in many areas, but rewilding is an opportunity for us to reconsider our goals. An opportunity to work towards a situation where nature leads, rather than humans.”

A rewilding showcase

Founded in 1914, the Swiss National Park shows what can be achieved when people take a back seat in protected area management and allow natural processes to reshape landscapes. Probably the oldest European rewilding initative, the park was also an early member of Rewilding Europe’s European Rewilding Network. Keystone species such as ibex and bearded vulture have been reintroduced, with iconic herbivores such as chamois, red deer and ibex helping to maintain half-open, half-forested areas through their grazing. Over time wolves, lynx and bears have returned to parts of Switzerland and have all been sighted in the park.

“Over 100 years ago the progressive Swiss National Park authorities decided they would let nature do the job of managing itself,” says Frans Schepers. “Today you can see the benefits – wild nature is flourishing, with a minimum of intervention. This contrasts greatly with the situation in many of Europe’s protected areas, which are still very actively managed. The case of this pioneering park shows that it is not only possible to do things differently, but preferable too. ”

Game-changing role

Today rewilding is establishing itself as a new and inspirational conservation narrative, as its practice, impact and benefits are amplified across Europe. Against the backdrop of COP26, the EU Green Deal and the Restoration Directive, and strongly growing interest in rewilding from the financial sector, philanthropic institutions and corporations, our generation could be the first in human history to upgrade rather than downgrade European nature.

As part of a far more expansive, better connected and wilder network of natural sites and corridors, Europe’s protected areas could play a game-changing role in this transformation. When they were first established just over a century ago, the continent’s national parks focused people’s minds on both the importance and wonder of European wild nature. Rewilding could see them play a seminal role in conservation once again.