ARK Nature’s Circle of Life project, which aims to increase the availability of carrion in nature, began life as a groundbreaking way of helping endangered scavengers in the Netherlands. Rewilding Europe, which has already adopted the Circle of Life approach in its rewilding areas (by enabling wildlife comeback and reintroducing herbivores), is now working to scale up the project across Europe by promoting best practice, fostering dialogue and encouraging collaboration.

Missing link

On starting this blog I realised that almost a decade has passed since ARK Nature’s Dutch project “Dood doet Leven” (“Circle of Life”) began. This timescale extends back even further when you take into account the first booklet bridging carrion with conservation, which was published in the Netherlands in 2005. In line with a lot of conservation work, the project has needed time to bear fruit, but I think it’s safe to say we’re already achieving promising results.

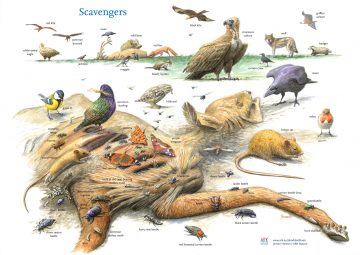

A scavenging vignette typically presents a dead animal, with scavengers opening up its carcass and the flesh being consumed by an array of other animals. For the majority of people, this is not the most pleasant of scenes. But on closer and more considered inspection, the necessity of carrion in nature quickly becomes apparent.

Carrion should be a normal part of the circle of life. But across the European continent today, wild herbivore carcasses have become a rare commodity. Wilderness has become arable land, populations of wild grazers are often managed at low densities, and legislation demands the immediate removal of dead livestock. As a result, much of the biological “waste” has disappeared from the European ecosystem.

The devastating results of this disappearance of wild carrion can be found everywhere. We are now witnessing a massive decline of scavengers, with struggling vulture populations dependent on artificial feeding stations. Many scavengers are now at risk of poisoning by lead ammunition and veterinary drugs like diclofenac (veterinary diclofenac is a drug used to treat livestock like cows and pigs; when livestock carcasses are left in nature, vultures feed on them, ingest the diclofenac, and are poisoned and die).

Last but not least, the harvesting of wood and the decline in wild herbivore populations is leading to a deficiency of minerals in sandy soils. The absence of essential minerals for plant growth is having a massive impact on the food web, with the effect exacerbated by anthropogenic nitrogen deposition.

A groundbreaking approach

ARK Nature has always been a pioneering NGO, working from vision to practice since it was founded in 1989. In 2008, for the first time ever, we established a publicly viewable scavenging webcam with the Dutch State Forestry Service.

Through the webcam, thousands of people watched the decomposition of road kills (mainly roe deer). The responses where overwhelmingly positive. People enjoyed seeing buzzards, crows, magpies, foxes and beech martens enjoy their free meal. Well, not exactly free. There was significant interaction between individuals and species, such as magpies picking the tail feathers of buzzards, and foxes chasing away beech martens (a roe deer of 18 kilogrammes is clearly a prize worth fighting for).

Following the positive feedback from the scavenging webcam we were able to scale up the project, with pilot areas established in the southern part of the Netherlands. A growing number of nature organisations chose to give road kills a final resting place in nature, rather than an immediate, one-way route to destruction, as is the case in most of Europe.

Several public surveys have since shown that Dutch people are increasingly acceptant of such an approach. Of course, not everyone wants to see a carcass in nature. But education has helped a great deal, generating both understanding and enthusiasm.

Online videos have helped to educate the Dutch public about the importance of carrion in nature.Online videos have helped to educate the Dutch public about the importance of carrion in nature.With ecologists at the Brandenburg University of Technology starting the Necros Project in eastern Germany at roughly the same time, we soon joined forces. Research by many students provided interesting results and fresh insight. Until now more than 100 bird and mammal species have been found to benefit from carrion in Western Europe. This is an astonishing figure, and we are only talking about vertebrates. The number of invertebrate species could be in the thousands. As you can see, there is still much for us to discover.

Closing the circle

The ecological insights and experiences that we have gained through the Circle of Life project have been used to create a brochure for Dutch conservationists, ecologists and policy makers. Several nature organisations are starting their own projects. A growing number of people involved in the removal of road kills and hunting management are also becoming enthusiastic about leaving dead wildlife in situ to be scavenged naturally.

Together with Rewilding Europe and several other partners, we recently published a European version of the Circle of Life brochure. To support Europe’s scavengers, this provides readers with both ecological insight and practical ways of bringing carrion and scavengers back into conservation.

As examples of such an approach, more road kills could be returned to nature. Hunters can use lead-free bullets and leave behind the intestines and other non-used parts of their kills for scavengers to consume. And in the case of animal kills for population management, whole carcasses could be left behind. The overarching, long-term objective is the creation of large areas where wild herbivores can roam free again, with large predators preying on them and thereby providing carrion for scavenging communities. This is what we are really missing in many parts of Europe.

By collaboratively adopting the Circle of Life approach, we can immediately provide food for all kinds of scavengers across Europe. We can start research to fill in knowledge gaps concerning carrion-based ecology. We can find ways to change relevant regulations so that scavengers benefit. And together we can scale up pilot areas until large expanses of land are created where natural processes impact the landscape and local ecology unhindered. When this happens we will have gone some way to closing Europe’s circle of life.

With vulture populations now growing in southern Europe, increasing numbers of vultures are visiting the Low Countries. In most cases they stay only a couple of days and return with an empty stomach. The return of road kills to nature can provide them with food, enabling longer stays. In 2012, one griffon vulture stayed for six weeks in a stone quarry on the Belgian-Dutch border when such kills were provided.With vulture populations now growing in southern Europe, increasing numbers of vultures are visiting the Low Countries. In most cases they stay only a couple of days and return with an empty stomach. The return of road kills to nature can provide them with food, enabling longer stays. In 2012, one griffon vulture stayed for six weeks in a stone quarry on the Belgian-Dutch border when such kills were provided.

- Learn more about the Circle of Life (Dutch only) and on the Rewilding Europe website.

- Circle of Life videos.

- Necros Project videos.