The Dalmatian pelican continue to show signs of recovery within their range in southeast Europe, including the Danube Delta rewilding area. Yet, their fragmented populations pose a problem for the species’ long-term stability. Here’s an overview of our actions and results so far, to support the comeback of these gentle giants.

Wetland icon

A flock of Dalmatian pelicans in full flight leaves a lasting impression. With an albatross-rivalling wingspan of over three metres, a bill up to 45cm long, and weighing around 12kg, these primeval-looking leviathans are an impressive sight. Despite their size, they cut a graceful shape in the skies above Bulgaria, Greece, Romania and Ukraine – the Mediterranean-Black Sea flyway. A crucial migratory motorway for this near-threatened species, and home to around 50% of the global population.

A flock of Dalmatian pelicans in full flight leaves a lasting impression. With an albatross-rivalling wingspan of over three metres, a bill up to 45cm long, and weighing around 12kg, these primeval-looking leviathans are an impressive sight. Despite their size, they cut a graceful shape in the skies above Bulgaria, Greece, Romania and Ukraine – the Mediterranean-Black Sea flyway. A crucial migratory motorway for this near-threatened species, and home to around 50% of the global population.

It’s the setting for an ambitious five and a half-year programme to reduce the threats posed to the birds, while improving their habitat at 27 sites across this part of their range: the Pelican Way of LIFE initiative, coordinated by Rewilding Europe.

While not true migratory birds in south-eastern Europe, they are dispersive with interconnected populations, underlining the need for some large-scale, joined-up thinking when it comes to their long-term conservation. Climate change is altering their movement patterns, with a growing tendency to stay close to breeding grounds. It’s likely that more will become resident in areas, as opposed to making short migrations, and so underlines the importance of optimising the suitability of conditions at each individual site.

Indicator species

The Dalmatian pelican acts as an ambassador for a rich and interconnected wetland system in this part of Europe. As an iconic indicator species, supporting the comeback of the Dalmatian pelican can indirectly help to restore vast swathes of wetland, lake and marshy habitat that is likely to have a positive ripple effect on a multitude of other species.

Finding new ways to boost its numbers can reinvigorate an ecosystem, and shine a light on the need for more formal protection of these habitats, the benefits of large-scale wetland restoration and the value of natural processes. As well as underlining the necessity of healthy fish populations, which leads to rivers being restored and rewilded. The Dalmatian pelican can do all of this, while taking on an ambassadorial role in promoting the need for well connected, rewilded wetlands across Europe.

Finding answers

There are many knowledge gaps that need to be filled, to inform better conservation decision-making and improve the species’ chances of survival. What is the true impact of powerline collisions?

Collisions with power lines remains a problem, and the programme is investing considerable time and resources into the identification of high-risk cables and mitigation techniques, primarily using bird diverters – reflective pieces of plastic attached to the pylons.

And what are the population sizes, and trends for movements and migration? What are people’s attitudes to the birds – how are they perceived throughout the flyway, particularly by fisherman and fisheries? How easily can they recolonize former or new breeding sites? What is the extent of persecution?

Partners of the Pelican Way of LIFE – the Bulgarian Society for the Protection of Birds (BSPB), the Hellenic Ornithological Society (HOS), Persina Nature Park Directorate, Rewilding Danube Delta and Rewilding Ukraine and the Romanian Ornithological Society (SOR) – seek to answer these questions, along with many more. And in doing so, it will create more fertile conditions in the future for the species’ proliferation – and bolster a number of currently small, isolated populations to prevent the very real prospect of local extinctions.

A helping hand

While finding answers, it is instrumental for the support of the Dalmatian Pelican’s recovery to create new breeding colonies on the Ukrainian side of the Danube Delta to stabilise and extend the population in the region.

The pelicans in the Balkans have their traditional breeding sites ranging in size from one nest, to over 250 – sitting atop of large jumbles of sticks, stones, mud, reeds, grasses and feathers; preferring sheltered spots in open or slightly concealed areas. So far, they mostly breed in small (up to 10-20 nests) and scattered colonies.

With natural nesting sites increasingly being damaged by storms or consumed by flooding, giving the pelicans an initial helping hand with nesting platforms cushioned with reeds has proven to be a highly effective tactic. While their natural habitat is being restored, it’s a critical first step in getting them to settle in the area, with the ultimate aim of natural nesting in the years to come without human intervention.

2020

Breeding pairs

Thirty pairs were recorded nesting on one newly-built platform in Bulgaria’s Persina Nature Park during 2020 – raising a record-breaking 40 chicks. Key to the success have been regular monitoring patrols on land and water, creating a peaceful sanctuary for the sensitive birds – essential during the breeding and nesting seasons.

Better protections have also contributed to a gradual rise in the number of breeding pairs in the Romanian portion of the Danube Delta – estimated to be between 446 and 486 in 2020. Over the last decade numbers have ranged from 252 to 432.

And surveys in Ukraine are also promising, with 58 observed in the Delta during May 2020 – up from just 7 recorded in 2018. And a record-breaking 155 were counted overwintering throughout the winter of 2019-2020 in the wetlands of Lake Kugurlui – the only site in Ukraine where Dalmatian pelicans are known to have successfully nested in recent years. And critically, the birds have begun to establish new breeding colonies, giving hope that – if the right kinds of conditions are created – further population increases are likely.

Winter counts

Dalmatian pelicans depend on still waters brimming with fish to breed, in areas undisturbed by human activity with an abundance of shallow water. Feeding exclusively on fish, they typically float on the water to hunt; their large, webbed feet acting as powerful propellers – before plunging beneath the water to scoop up prey with their enormous mandible and pouch.

A total of 567 were counted in their preferred wintering areas in southern Romania at the end of 2020, along with an additional 62 in the Danube Delta and 812 along the Bulgarian Black Sea coast. The latter was a considerable increase from 2019 when 483 were spotted. Along with those carried out in Ukraine and Greece, the labour-intensive surveys build-up a picture of the birds’ distribution over an enormous area, involving many hours in the field accessing remote areas over difficult terrain. A drone plays an important role alongside the boat, and various other modes of transport.

2021

Satellite transmitters

In January of this year, experts from the Bulgarian Society for the Protection of Birds (BSPB) successfully trapped and ringed wild adult Dalmatian pelicans for the first time on the Atanasovsko Lake, with further work planned to fit a total of 25 birds with satellite transmitters across the entire flyway area.

This will be a crucial action for the programme in amassing new data about locations where they congregate, feed and roost, as well as providing insights into movement patterns and causes of mortality. The BSPB also joined members of the Persina Nature Park Directorate to check and improve the nesting conditions on Persin Island – the wooden platforms providing a precious refuge.

In February the first Dalmatian pelican in Bulgaria was fitted with a GPS tag. Weighing just 33 grams, it’s placed with precision on the wing, with no hindrance to flight or swimming. Further satellite-tagging took place in western Greece during April, at the Messolonghi lagoon.

Movement patterns

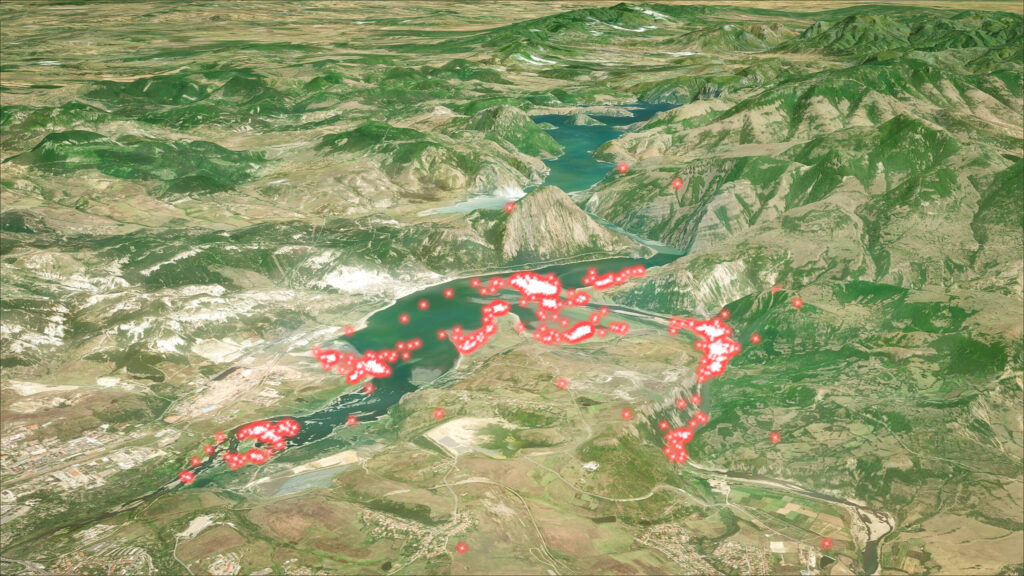

With three Dalmatian pelicans now satellite-tagged, we’re beginning to form a deeper understanding of movement patterns and behaviour. Maria, the first Bulgarian bird to be tagged has already been very active – visiting Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey in the last few months covering up to 285 km in one day. This emphasises the need for cross-border protections and a web of suitable habitat to sustain them as they criss-cross the continent.

Maria has been spending a lot of time in our Danube Delta and Rhodope Mountains rewilding areas, arriving in Bulgaria’s Studen Kladenets dam basin on the 22nd April. After leaving the Rhodopes on the 4th May, she landed in the Delta three days later in the Lacul estuary, before heading back along the river to the same spot in Studen Kladenets; a round trip of 1,400km over nine days. Her subsequent flight south to Turkey’s wetlands in June clocked up another 1,400km.

The second and third members of the tagged trio are Greek-based birds, Anna and Maestros. Anna has already had to overcome a serious infection, covering 722 km during her first two months back in the wild following rehabilitation. She’s been spending a lot of time in the Natura 2000 site between Vonitsa and the island of Lefkada – a popular foraging and resting area. And data from Maestros’s movements is also helping us to determine whether separate colonies in Western Greece are connected or not – valuable information when you have many fragmented populations.

Promising results

This year, the breeding season in the Park was in full swing for a sixth consecutive year, with all four of the artificial sites – by the marshes and in the drained swamp – occupied for the first time. New life on its way. And the good news continued in March, with a record-breaking number of 64 recorded on two of the nest sites in the Peschina Swamp – up from just seven pairs in 2016.

In mid-May, the fourth South-Eastern European Pelican Census took place, coordinated by the Hellenic Ornithological Society (HOS). Members of the BSPB visited key wetlands across Bulgaria, with the greatest concentration of the Dalmatian species observed in the swamps of Persin Island. The study highlights the importance of trans-border cooperation as the Pelican Way of LIFE initiative seeks to further protect these scattered populations across four countries, while furthering our understanding of their ecology.

Simultaneously, a separate count was underway in the Ukrainian part of the Danube Delta, implemented by Rewilding Ukraine in cooperation with the Danube Biosphere Reserve {DBR]. The lakes of Kitaj, Yalpug, Katlabuh, Cahul, Kugurlui and Lung were all visited, along with additional coastal areas. While over 2,000 Great White pelicans were recorded, only 83 Dalmatians were spotted, highlighting the species’ precarious conservation status. Efforts to increase their numbers in Ukraine were given a boost in June, with two reed-covered breeding platforms put in place to encourage the establishment of new colonies.

Back in Bulgaria, a new nesting colony was established on an artificial island near the city of Tutrakan – the birds seemingly attracted by the sight of three life-sized model pelicans on the decking. This prime piece of restored real estate sits in the internationally important wetland of Kompleks Kalimok.

Future memories

This month, the first nature protection festival dedicated to the Dalmatian pelican took place, organised by our partner Persina Nature Park Directorate.

Educating and inspiring the next generation of conservationists and rewilders is a key component of the Pelican Way of LIFE initiative, and recently, school visits have resumed after being postponed due to the pandemic.

Stimulating an interest in the birds is vital for their future protection, after all, you can’t protect what you don’t know or care about. Pelican Way of LIFE is working across borders with many different stakeholders to generate that sense of care.

Pelicans may be ambassadors of healthy wetlands, but we need people to be ambassadors for healthy pelicans too. Thanks to the time taken in tagging with satellite transmitters, detailed movements of individual birds can be followed – each one an unfolding story in itself to stimulate that interest. And as a highly visible, charismatic species, the Dalmatian pelican has a lot of tourism appeal – featuring on the birdwatching bucket list of many. Support their comeback and you develop a growing sector of the local economy.

The programme is a compelling example of what can be achieved through problem-solving across many local sites, in a transboundary cooperation, to collectively benefit a species on a continental scale. It is weaving together a new framework for the Dalmatian pelican’s long-term resurgence, so that more pelican encounters can be etched indelibly in the memory for generations to come.

More information:

The Pelican Way of LIFE initiative is funded by the EU’s LIFE Programme, and co-financed by the Arcadia Fund, the UK-based charitable trust of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin.