One of Europe’s most highly regarded Eurasian lynx experts talks about the comeback of this beautiful yet elusive feline.

Eurasian lynx and rewilding

Wildlife comeback is one of the core objectives of rewilding, whether through reintroduction and restocking, or by creating the right conditions for species to return of their own accord (for example, by enhancing the availability of prey or restoring habitat). When it comes to European rewilding and the Eurasian lynx, both of these measures apply.

The Eurasian lynx is found as a breeding species in two of Rewilding Europe’s operational areas: the Velebit Mountains in Croatia – where the LIFE Lynx initiative, a European Rewilding Network member since 2019, is now reintroducing animals – and the Southern Carpathians of Romania. Individuals are also recorded in the Rhodope Mountains from time to time. While there are no confirmed sightings of Eurasian lynx in the Oder Delta as yet, the Western Pomeranian Nature Society (ZTP) is reintroducing lynx in the forests immediately to the east of the delta, and it is hoped that these animals will eventually move westward.

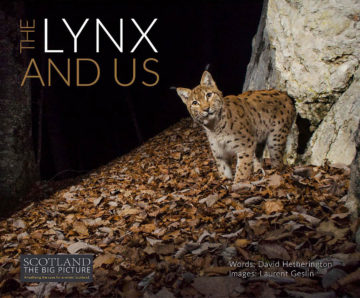

One of the episodes of the TV series “Europe’s New Wild” (titled “Return of the Titans”) – which is set to be broadcast at the end of this summer – features the reintroduction of two male Eurasian lynx (Alfi and Wrano) to the Palatinate Forest of southwest Germany. We caught up with David Hetherington, a leading expert on Eurasian lynx and author of the widely acclaimed publication “The Lynx And Us“, to find out more about Europe’s “big cat”.

As you mention in the introduction to your book, the Eurasian lynx is a bit of a mystery to many people. Can you tell us a little more about this special animal?

There are four lynx species in the world, the Canada lynx and bobcat in North America, and the Eurasian lynx and the Iberian lynx in Europe. They all have the same body shape, with tufted ears, short tails, long legs and a spotted coat.

The Eurasian lynx, which is twice as large as its cousins, prefers to prey on deer, especially roe, while the other lynx species tend to prey on smaller mammals such as rabbits and hares. You could think of it as filling roughly the same ecological niche as the larger cougar in North America, which is also a solitary ambush predator of deer.

The Eurasian lynx is typically crepuscular, which means it is most active at dawn and dusk. This means that many people who live alongside Eurasian lynx are sometimes unaware that it’s even there. I’ve always been fascinated by Eurasian lynx, precisely because they have an almost mystical aura about them.

How is the Eurasian lynx doing in Europe?

The Eurasian Lynx has a very wide geographical range, extending from Western Europe to Eastern Asia. In Europe, hunting and habitat loss has seen the animal’s distribution shrink severely over the last few centuries. Today, however, the situation is improving, thanks to better protection and various reintroduction efforts, such as the one featured in Europe’s New Wild episode ‘Return of the Titans’. There are still huge areas of Europe which once supported Eurasian lynx and could do again.

In areas where the Eurasian lynx is present, how does it benefit local wild nature?

The Eurasian lynx is a keystone species, which means it can have a high impact on its environment, relative to the size of its population. The relationship that lynx have with their environment is actually very complex and can vary from landscape to landscape. However, we know that in Sweden and Finland, Eurasian lynx prey on or displace smaller carnivores such as red foxes. This, in turn, benefits other species, such as black grouse, capercaillie and mountain hare, on which the fox typically preys.

Eurasian lynx also leave behind the carcasses of their kills. This provides food for scavenging species ranging from maggots through to eagles and bears. And the carcasses eventually break down, which means nutrients go back into the soil, which provides opportunities for plants to grow.

Can the reintroduction of Eurasian lynx benefit people?

The reintroduction of iconic wildlife species generally helps drive wildlife tourism. With the Eurasian lynx things are slightly different, because it is really hard to spot. It won’t come to bait that has been left close to a wildlife hide, for example, as is the case with other carnivores such as bears.

However, German national parks are using Eurasian lynx as a marketing icon, where it has come to symbolise wild beauty. On a personal level, I find it much more thrilling to walk through a habitat where I know lynx are present. A healthy Eurasian lynx would never attack a human, but their presence reinforces the fact that you’re in a properly wild area.

What does the future hold for the Eurasian lynx in Europe?

The Eurasian lynx population in Europe has been recovering since the 1960s, and I expect this trend to continue. However, Europe is a busy continent and these animals will continue to face challenges. One of the biggest of these relates to a lack of connectivity in the lynx’s habitat – roads and rail lines, for example, make it difficult for the animal to spread out, find a mate, and recolonise territory. Traffic accidents are responsible for many lynx deaths.

Can the recovery of the Eurasian lynx in Europe teach us anything about living alongside other carnivores?

Yes, definitely. There are three main large carnivores in Europe – lynx, bears and wolves. Of these, reintroducing lynx is the least problematic; they aren’t a physical threat to humans, and they cause fewer problems with livestock. Bears and wolves have the potential to cause far more damage. So when it comes to reintroducing carnivores, starting with lynx is the logical first step – a bit like learning to swim in the shallow end, and then going deeper. As Europe becomes wilder people’s mentality is slowly changing – the Eurasian lynx is part of this trend.

Do you have a favourite lynx experience that you can tell us about?

I was helping out with the radio tracking of a Eurasian lynx in the Swiss Alps quite a few years ago. We’d been out with the antenna for ages, without getting a signal, and everyone was a bit frustrated. Then we realised that some nearby cliff faces were blocking the signal, adjusted the antenna, and got a really strong hit right away. I scanned the ravine opposite us, and saw this little lynx face staring at us from some vegetation. If we hadn’t had the technology I’d have had no idea it was there. It was a really primal experience and makes the hair on the back of my neck go up thinking about it even now.

As you say, Eurasian lynx are hard to see in the wild. How can people learn more about them?

If you’re fortunate enough to live near a place where Eurasian lynx live, go out and walk the trails – you never know, you might be lucky. If there are some local rangers, talk to them about the best spots for an encounter. And in some places, such as Slovakia, there are some good guided lynx-tracking experiences.

Most of us will need to look online. The multilingual KORA website is a good resource, and has information about other European carnivores too.

And of course, you could buy my book. There are three places to purchase it: through Scotland the Big Picture, from Amazon, and through NHBS. The latter is probably the best option if you live outside the UK and want to keep postage costs down. The book essentially explores, in a balanced, non-technical way, how Eurasian lynx and people interact in places where the animal lives, with some beautiful photos from Laurent Geslin, an award-winning photographer based in Switzerland.