As part of the ongoing LIFE Vultures project, a growing number of griffon and black vultures in and around the Rhodope Mountains rewilding area are being tagged with GPS transmitters. The geospatial data these transmitters provide will be critical to the comeback of these magnificent yet endangered birds.

Driven by data

Locked between the valleys of the Rivers Arda and Maritsa, the Eastern Rhodope Mountains are the last stronghold of Bulgarian vultures. The area is home to the only griffon vulture breeding site in the entire country, while black vultures, although sadly extinct as a breeding species in Bulgaria, are regular visitors from their breeding colony just across the border in Greece.

Starting in 2016, the five-year LIFE Vultures project was developed by Rewilding Europe, in collaboration with the Rewilding Rhodopes Foundation and a range of other partners. Focusing on the Rhodope Mountains rewilding area in Bulgaria, as well as a section of the Rhodope Mountains in northern Greece, the aim of the project is to support the recovery and further expansion of the black and griffon vulture populations in this part of the Balkans, mainly by improving natural prey availability, and by reducing mortality through factors such as poaching, poisoning and collisons with power lines.

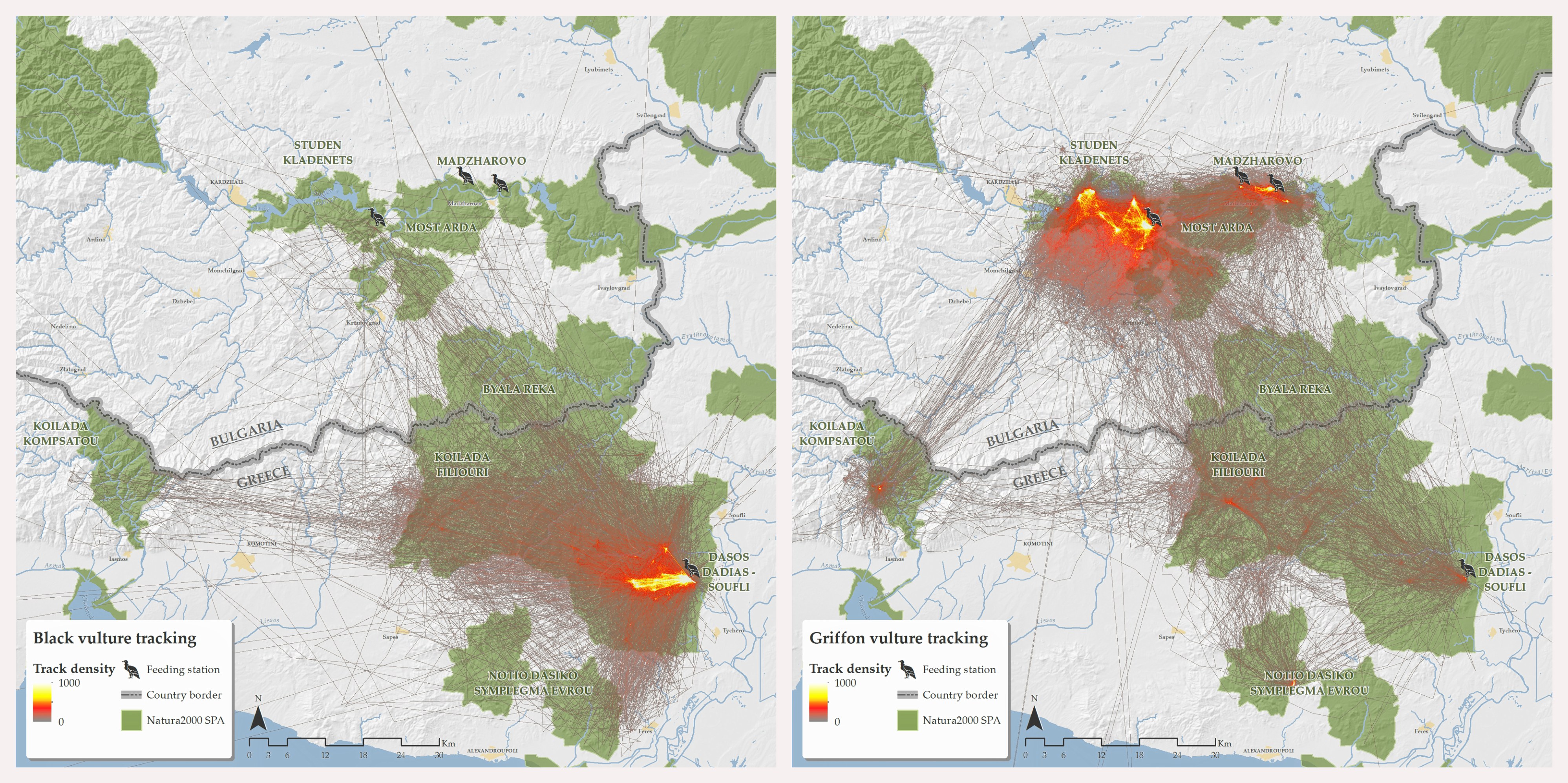

Essential to maximising the success of the LIFE Vultures project is the tagging of black and griffon vultures with GPS transmitters. As GPS data is systematically fed into a Geographic Information System (GIS), together with a range of other variables, so the rewilding team and their partners are gaining groundbreaking insight into the movement of vulture populations in the monitoring area, the various threats that they face, and the best ways to support the birds’ comeback.

“We can use the GIS to check for bottlenecks in the vultures’ flight paths, for example,” explains Jelle Harms, Rewilding Europe’s GIS Data Manager. “This can help us to identify where the risk of collision with pylons and power lines is greatest. It can also help pinpoint the best locations for artificial nests, when it comes to encouraging black vultures to start breeding again in Bulgaria.”

The Rewilding Rhodopes team has already mapped most of the pylons in and around the rewilding area, and identified the most dangerous to the vultures from the GPS transmitter data.

“Some of the pylons have been insulated and bird diverters placed on the electrical wires,” explains Volen Arkumarev, a member of the Rewilding Rhodopes team and a conservation officer with the Bulgarian Society for the Protection of Birds (BSPB). “We have also been working with local electrical companies to get lines rerouted underground in sensitive areas.”

The GPS data also helped to locate another potential problem area for Balkan vultures in Greece, outside a national park. The birds are drawn here due to the supply of livestock carcasses, but wind farm projects pose a growing threat. Vultures have such large blind spots in their visual field that they cannot see objects directly ahead when they fly. This explains why they frequently collide with conspicuous structures such as wind turbines and power lines, despite having incredibly sharp vision.

“We can use the GPS data to have wind farm projects stopped or relocated,” says Arkumarev. “It’s a critical tool.”

A progressive project

The tagging being carried as part of the LIFE Vultures project is the first of its kind in the Eastern Rhodopes for griffon vultures, and the biggest for black vultures in the whole of the Balkans. The aim is to eventually fit 20 griffon vultures and a similar number of black vultures with transmitters.

At the moment the Rewilding Rhodopes team have tagged 15 griffon vultures (10 were tagged this May), while 11 black vultures have also been tagged in Dadia National Park in northern Greece. More than 170,000 data fixes have now been obtained from these transmitters. Another tagging session has just taken place, using new collars containing accelerometers. By indicating the position of the vulture’s head, and the general flight attitude of the bird, these should provide data of increased ecological value.

The GPS data collected to date has already been used to generate a number of fascinating tracking maps from the GIS database. They reveal that both griffon vultures from Bulgaria and black vultures from Greece make daily feeding trips across the Bulgarian-Greek border.

“The birds are mainly visiting protected areas in both countries, although the maps are a little biased as these areas were where the birds were originally captured and tagged,” explains Harms.

Rewilding Europe’s GIS Data Manager is excited by the huge potential of the vulture tagging endeavour.

“We will collect a vast amount of data through this project,” says Harms. “This will be analysed as we go along. The hardest part is knowing which questions to ask to extract the most valuable answers. That and capturing and tagging the vultures in the first place.”

Labour of love

Trapping vultures to fit GPS transmitters is no easy task, as Volen Arkumarev knows only too well from personal experience. In the Rhodopes rewilding area vultures are trapped in a cage which is baited with carrion – once the birds are inside the cage, a trapdoor is operated by a rope.

“Griffon vultures are big, and they’re smart, and they can be very suspicious, so it can be really difficult to tempt them inside the cage, especially at times when there’s an abundance of other food,” explains Arkumarev. “The birds have to be completely inside the cage, as there can be no risk of injuring them.”

Due to the late arrival of transmitters from a supplier, members of the Rewilding Rhodopes team attempted to tag some griffon vultures in the rewilding area (near the town of Madzharovo) last summer. After getting up every day at 3 o’clock in the morning for 40 consecutive days, they managed to trap three birds.

“You have to wait in the hide, ready to pull the rope, without talking or moving,” says Arkumarev. “It’s not the most pleasant experience, especially when it’s dark and there are mice running around your feet.

“When you catch the vultures, they also tend to vomit a lot,” continues the Rewilding Rhodopes team member with a laugh. “But we still like them!”

Up close and personal

When it comes to managing the LIFE Vultures project GIS, Jelle Harms spends most of the time in his Amsterdam office. Yet the Dutchman has still been afforded a unique insight into the behaviour of many of the tagged Balkan vultures.

“For me, the best thing about this GIS work is getting to know the birds through the data they supply,” says Harms. “You can see the huge efforts that these vultures put in to survive and raise offspring. We have already learned a lot about the amazing wanderings of young vultures.”

One such bird was Miko, a young male griffon vulture, who was found running along the street of a Bulgarian town with an injured wing in the summer of 2016. He spent a month in a rehabilitation centre, where he was tagged prior to being released.

“We took Miko to a feeding station and opened his cage, but he didn’t want to fly,” says Arkumarev. “Eventually he ran under a bush and just stayed there. We were worried that he had forgotten how to flap his wings.”

Miko spent the next two weeks on the ground, living in the bushes, being fed small pieces of meat by hand.

“We were losing hope that he would ever fly again,” says Arkumarev. “It was decided that he should return to the rehabilitation centre. On the morning of his return, we arrived to see Miko on one of the highest nearby cliffs. He had made his first flight since the injury!”

Eventually, Miko found a friend and the pair learned the ways of vultures together. GPS data showed the young male wandering farther and farther afield, first to Greece, and then to southern Turkey. And then, following the Black Sea Coast, the tracking data suddenly stopped.

“We don’t know what happened to Miko, but the lives of these young vultures are filled with dangers,” says Arkumarev. “Sometimes a second chance just isn’t enough to make it through into adulthood.”

A slightly happier vulture tale is that of Zvezdi, who may also turn out to be Zvezda (it’s hard to tell if a vulture is male or female). After hatching near the town of Madzharovo last year, in the Rhodope Mountains rewilding area, GPS data revealed Zvezdi journeying as far south as Saudi Arabia, where the young vulture stayed for six months. This spring saw the bird relocate to eastern Turkey, where he/she has stayed until recently, foraging in the high mountains at around 3000 metres.

“The movement of some of these birds is just incredible,” says Arkumarev. “Zvezdi has started to move south again now, so we’re waiting to see where he/she goes. Will it be south to the desert again, or a return to his/her Bulgarian birthplace? We’ll keep you updated!”

The human connection

As well as supporting vulture comeback, the LIFE Vultures project also aims to increase public awareness of vulture conservation.

“The GPS tagging of Balkan vultures empowers us with knowledge,” says Arkumarev. “It helps us to take the best conservation measures. But it’s also a great way for the public to learn more about vultures, to see how they live and behave, and to appreciate how special these birds are.”

The Rewilding Rhodopes team regularly post inspiring stories about tagged vultures on their Facebook page to keep followers updated, while a number of Bulgarian vulture photo exhibitions have also been held. In the future a semi-live online vulture tracking map may be created, although maintaining bird safety will necessitate the use of a time lag. There are also plans to install a camera in a vulture nest this autumn/winter period.

“Some of these tagged vultures are real adventurers,” says Arkumarev. “Others prefer to stay in the area where they were born. Either way, our tagging work will hopefully lead to more of these beautiful birds in the Balkan skies, and more people appreciating them.”