Against the backdrop of rising global temperatures, biodiversity decline and the impact of COVID-19, the rewilding of Europe’s cities and surrounding areas can benefit people in myriad ways. The protection and enhancement of natural forests is key to delivering such benefits.

Our need for nature

The tropical temperatures experienced by residents across large swathes of Europe last week saw millions, especially those living in cities, flock to nearby parks, forests, rivers and lakes. When the mercury rises, it’s our first instinct to leave the concrete and tarmac behind and head into nature. Establishing or reinforcing people’s connection with wild nature is increasingly recognised as critical to their mental and physical health, a fact which has been reinforced by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Rewilding Europe does not focus directly on urban rewilding. However, there are many linkages between urban areas and surrounding landscapes. The process of urbanisation and rural depopulation is still ongoing in Europe; with more and more Europeans living in urban areas, the need to create and enhance green spaces around and within such areas has never been greater. The protection and enhancement of natural forests (essentially forests that have developed without the interference of man) has a key role to play in this regard.

Natural forests are key

Trees are integral to urban and peri-urban rewilding. Under the terms of the European Green Deal – a new strategy to protect and restore nature in the European Union – three billion new trees will be planted across the 27 member states by 2030, many in and around cities.

Such an ambitious scheme is laudable but needs to be carried out in the right way. Failed tree planting projects in Ireland and the Czech Republic have alienated locals, and the wrong tree in the wrong place can intensify forest fires and disease, and actually release more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Planting monoculture plantations on abandoned land typically creates forests that are of low biodiversity value. When these forests are harvested, the carbon they store is often released straight back into the atmosphere.

“We need to think less about afforestation and focus more on restoring the natural woodlands in all their diversity,” says Rewilding Europe Managing Director Frans Schepers. “Located close to cities, these complex mosaics of indigenous tree stands, woodlands, grasslands and other vegetation offer far more long-term value. We should refrain from massive tree planting schemes driven by the climate agenda in areas where land abandonment is happening, for instance. With natural forest regrowth already taking place, installing plantations would hugely damage open and half-open landscapes of high biodiversity value.”

The benefits of rewilding

Creating and enhancing spaces (such as natural forests) where nature can thrive in and around our cities provides multiple benefits and makes them eminently more liveable. In addition to directly improving human health and wellbeing, such spaces can also act as “green lungs” and carbon stores, significantly lower urban temperatures (increasingly important to counteract the effects of climate change), enhance aesthetic appeal, improve local economies through nature-based tourism and mitigate flood risk. And more wild nature can help to halt and reverse the ongoing decline in global biodiversity.

“Rewilding cities and surrounding areas makes sense on so many levels,” says Frans Schepers. “From viewing trees and plants from inner-city windows and rewilding gardens to restoring riverside habitats and peri-urban forests, every measure has a beneficial impact.”

European disparity

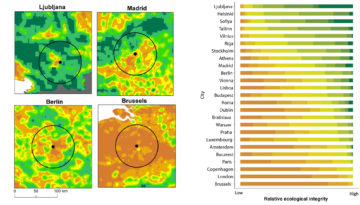

Co-authored by Rewilding Europe, a set of policy papers was published earlier this year outlining why and how European politicians should prioritise nature restoration in the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2030. As the culmination of a three-year, WWF Netherlands-funded programme to promote and strengthen Europe’s restoration agenda, the papers illustrate how many European capital cities suffer from poor ecological integrity – essentially the existence of ecologically functional, connected landscapes.

If wild nature is critical for healthy cities, then the ecological integrity rankings generated by programme researchers (see infographic) reveal some European capital cities to be far healthier than others, with Ljubljana ranking highest and Brussels lowest. Some of Europe’s capitals surrounded by the highest ecological integrity are well known as cities that actively promote a healthy living environment through the conservation of nature (the Paljassaare conservation area in Tallinn is an example).

The Ljubljana region, which enjoys good ecological connectivity to its hinterland and a relatively high functional diversity of species, serves as an example to others of the wider importance of developing green infrastructure throughout Europe, including urban green spaces.

The importance of natural grazing

Free-roaming or semi-wild herbivores, such as horses, deer and wild bovines, are key architects of such natural woodland ecosystems, contributing to biodiversity, facilitating spontaneous regeneration and carbon storage, and helping to minimise the threat of wildfire.

The ongoing GrazeLIFE project, which is currently evaluating the benefits of various types of land management involving domesticated and wild/semi-wild herbivores, has already shown that “herbiforests” – the name given to natural forests extensively grazed by populations of large wild herbivores – could significantly mitigate our climate and biodiversity crises.

“The time is right to rethink the idea of merely planting trees and instead support the landscape-scale development of herbiforests,” says GrazeLIFE Project Manager Wouter Helmer. “In and around cities, such forests should form a key part of reconnecting Europe’s urban residents with thriving wild nature and allowing them to benefit from it.”