Faced with economic and environmental pressures, the Sami people of Swedish Lapland are abandoning their traditional way of life. By developing partnerships that unite nature, culture and business, Rewilding Lapland is now working to offer them a more sustainable future.

A time of change

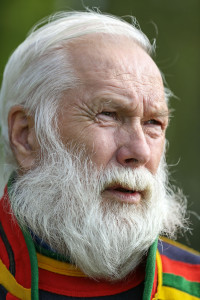

Moving slowy inside the smoke-filled confines of his wooden lavvu, Lars Eriksson is a man from a bygone era. Here, on the wave-lapped shoreline of Lake Gorgim, deep within the sweeping pine and larch forests of Swedish Lapland, the Sami elder still measures time by the season, not the second.

“The traditional Sami philosophy is to tread lightly across the land,” he explains, holding a snow-white reindeer pelt up to the light. “Our year, which has eight parts, was always divided according to the appearance of natural phenomena and changing animal behaviour.”

Living on the edge of Europe, the Sami people are a geopolitical anachronism. As the European Union’s only indigenous people, they have long regarded their homeland of northern Scandinavia and Arctic Russia as a borderless wilderness. Yet living in today’s world of intensive forestry, private land ownership and complex socio-economic issues, there is increasingly little room – and tolerance – for their habitual nomadism.

A short drive from Lake Gorgim, Eriksson lives in Flakaberg, with his wife and a herd of 300 reindeer. Around 130 kilometres north of Luleå, gateway city to Swedish Lapland, the village has no electricity. In fact, the white-bearded Sami clearly has an aversion to most modern technology.

“In the old days the Sami would go out on foot with their reindeer,” explains Eriksson, adjusting the leather belt around his colourful gakti jacket. “It was less stressful for the animals. But now the number of Sami involved in herding is falling. It may soon disappear forever if nothing changes.”

Shrinking herd

Reindeer husbandry was once an inextricable part of the Sami existence. Yet nowadays a growing number are involved in tourism, food production and other areas of the Swedish economy. When the Sami choose to abandon their reindeer, the decision is typically a financial one.

“Before we could make a good living from only 200 or 300 reindeer,” says Lars Eriksson. “Now a herder needs over 1000 to make a profit. The animals must be fed with food pellets, which can be hugely expensive.”

Lichens are organisms made up of fungi and algae working together in a symbiotic relationship. In natural conditions they form a vital part of the reindeer diet, especially during the harsh winter months of northern Europe. Unfortunately, in Swedish Lapland, they are becoming increasingly rare.

“Modern timber harvesting practices mean that many forests are cut down before arboreal lichens have had time to form,” says Cain Blythe, managing director of UK-based ecological consultancy Ecosulis. “Widespread fertilizer application to enrich the soil also damages lichens which have adapted to nutrient-poor conditions.”

Future focus

Officially launched in July 2016, Rewilding Lapland is now working to help select Sami communities maintain their culture of reindeer husbandry. This is being done through the protection of essential grazing land, the easing of seasonal reindeer migration routes, and the development of Sami-based tourism. In partnership with a group of around 275 landowners, a project has already begun to restore the Råne River, Sweden’s longest forest river, and associated waterways.

“In the past rivers were partially dammed by timber companies looking to float their logs downstream,” explains Håkan Landström, managing director of Rewilding Lapland. “By clearing away these obstructions, we lower the water to its natural level, thereby allowing reindeer to cross more easily.”

For many years, Lars Eriksson and his wife have run Årstidsfolket (literally “seasonal people”), a boutique travel company introducing visitors to the fascinating culture of the Sami. The success of this venture has shown the potential for scaling up culture-based tourism across the area.

“I’d love to see more tourists,” says Eriksson. “Of course you can’t stop time. But as an integral part of a Sami culture that people really want to experience, I still think reindeer herding has an important role as part of a wilder, less-managed Lapland.”

“There is fantastic potential to develop a nature and culture-based economy here,” says Håkan Landström. “Rewilding Lapland’s overriding goal is to show that relying on damaging industries such as forestry and mining is not the only way for local people to make a living.”

(Erikssons family run boutique travel company, Årstidsfolket, can by contacted at +46 925 330 23.)