Extensively grazed landscapes have a higher insect diversity, because of the many effects of natural grazing. Under the terms of the GrazeLIFE project, our partner ARK Nature is studying one of these effects more explicitly: the ecological value of clean manure.

Coordinated by Rewilding Europe, the three-year, European Commission-funded GrazeLIFE project aims to evaluate the benefits of various land management models involving domesticated and wild/semi-wild herbivores. The manure of herbivores that live freely in nature supports a myriad of insects and other organisms which, in turn, benefits all kinds of larger predator species. In this blog, Deputy Director of ARK Nature Esther Blom, explains how the resulting difference in biodiversity is an additional argument for natural grazing to be applied.

The state of insect populations

Beetles in newspaper headlines. Wild bees in the evening news. Entomologists on prime time talk shows. The latest research results on the state of insect populations in Germany and the Netherlands hit the Dutch media like a bomb in 2019.

As a biologist, I naturally considered the 75% decrease in the biomass of flying insects more than worth a headline and a necessary call to action. But the broadness of the response among Dutch people was a surprise. Here, at last, was an effective wake-up call on the current biodiversity crisis. For the average citizen, the lack of dead insects on car windows finally seemed to make this crisis real!

Reversing insect decline

A broad range of responses was formulated in the Netherlands. A “delta plan” for biodiversity was developed (a delta plan being a Dutch word invented for the closing of the Dutch river arms in the 20th century and now broadly used for cooperative, large-scale plans to diffuse big crises). The plan was jointly developed by nature organisations, scientists, the agricultural sector and the commercial sector focusing on what can be done in both agricultural and nature areas to improve biodiversity in general, and insects more specifically.

To create robust ecosystems that host plenty of insects, we obviously need to enhance wild nature and minimise the impact of surrounding intensive agriculture. This means areas that are more naturally managed, have more natural water levels, and that are well connected to other similar areas so that they are not isolated islands in green deserts.

Even flying insects like butterflies can only travel a limited distance in hostile environments such as maize fields, which means robust ecological connections are essential for their distribution. All these objectives are, of course, priorities for ARK Nature and other Dutch nature organisations. But this is long-term, challenging work – hectare by hectare, we have to try to turn the Netherlands into a more resilient ecological landscape.

Living manure

The good news is that there are also quick wins to combat the biodiversity crisis. And they have everything to do with (semi-)natural grazing. Extensively grazed landscapes have a higher insect diversity, because of the many characteristics and effects of natural grazing.

One of these characteristics is the fact that semi-natural grazers are hardly ever treated with insecticides against parasites. Due to his observational skills, my colleague Jeroen Helmer – self-made ecologist and widely acclaimed illustrator – discovered that it makes a world of difference on which pile of manure an insect lands, eats, predates, mates or lays its eggs. For parasites, the difference lies in the producer of the faeces – the grazer.

Almost all farm cattle and horses in the Netherlands are treated with medicines against parasites. These are medicines that are slowly released through the dung of the cattle, in the meadows where they graze. These toxic chemicals transform the dung into insect traps; the insects are still attracted to the dung, but their eggs don’t hatch.

Semi-natural grazers that live winter and summer in natural populations seldom need such treatment. They learn from other animals which medicinal plants they should eat when they have parasites. Their population densities are typically far lower (than occur with domesticated herbivores), resulting in a far lower risk of contamination. Only in rare cases are individual animals individually treated. Never as a precautionary measure, at the herd level.

The dung piles of these untreated animals teem with life, often only visible after placing the tip of your shoe into the juicy pile. Or after hours and hours of patient observation. Jeroen, as a patient, non-destructive observer, tells what he sees:

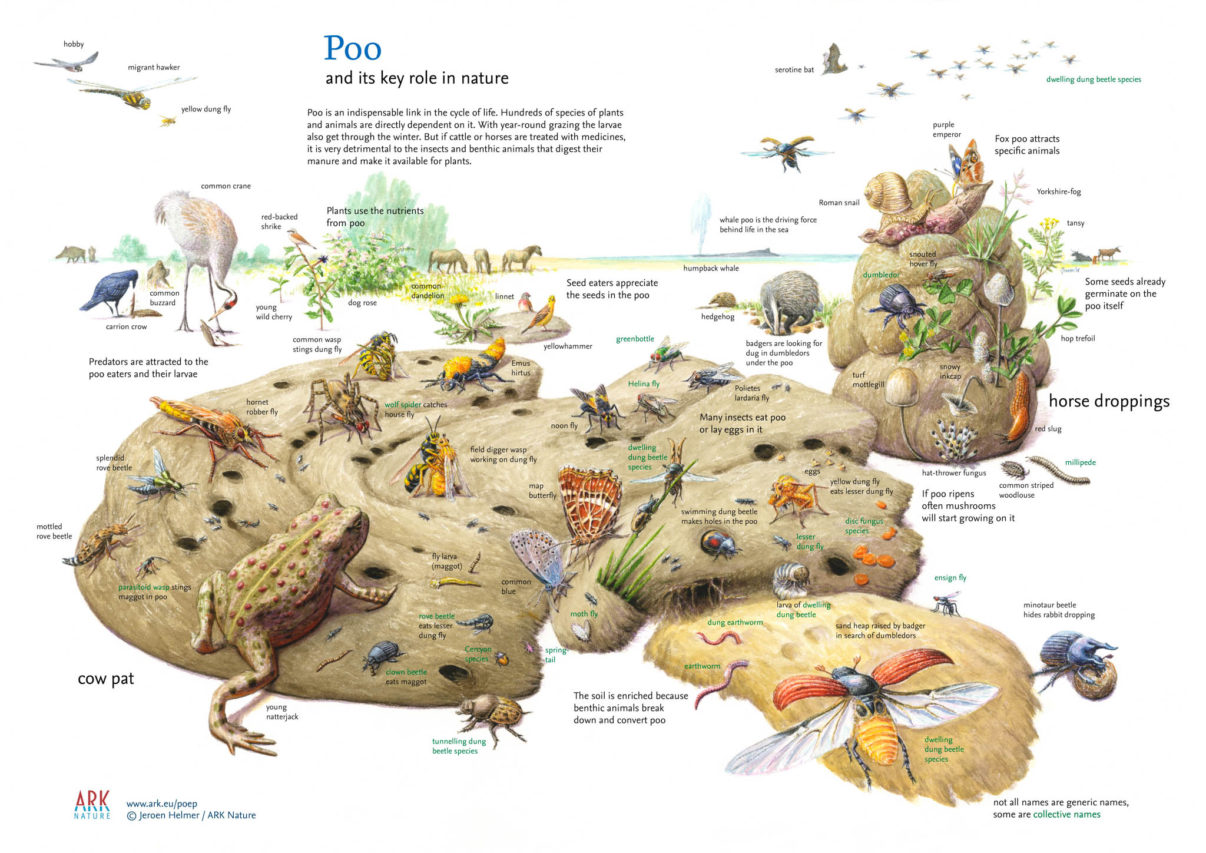

“It takes only seconds before fresh healthy dung of cattle or horse is colonised by flies such as the yellow dung fly and greenbottle. These flies lay eggs in the dung that hatch within days, after which the maggots start consuming the bacterial soup it contains.

In half a minute these flies are accompanied by the small dung-dwelling beetles. Their numbers rise to several thousands in a single pat. But the main job of processing the dung is done by the larvae of these beetles that can measure up to three times the size of their parents.

Crucial in the process of dung decomposition is the swimming dung beetle. Being, in fact, a water beetle, this species has “retrained” itself as a dung processor. They appear in fresh dung, going in and out, creating opportunities for all kinds of little dung eaters and predators such as rove beetles. These dung eaters and rove beetles enter the holes of the swimming dung beetles and find fresh dung, while the outside of the dung is drying out already. These holes also provide the oxygen required for the decomposition process. Dumbledor, tunnelling and minotaur beetles dig their holes up to one metre long in or next to dung, dragging a bit of it down to lay an egg into, thereby distributing the dung over a larger area.

This egg white bonanza attracts all kinds of predators. Numerous are the rove beetles. The little ones (smaller than 2mm) eat dung, but the bigger ones eat the larvae in it (up to small dung flies), while the one-and-a-half centimetre large mottled and splendid rove beetles eat the big blowflies and dung flies. The latter also risk being attacked by field digger wasps (in August), social wasps and hornet robber flies (in September), all specialist predators on dung fauna.

Dragonflies are often found in the vicinity of dung to catch flies attracted to it. All members of the crow family peck in dung for the larvae, especially those of beetles, tearing the dung apart, thus spreading the nutrients and minerals. So do badgers, digging up the dumbledors and turning over the pat for beetle larvae, as do cranes. Thrushes, woodcock, buzzard, shrews, greater mouse-eared bat and serotine bat also complete their diet with dung insects.

When dung lies for a while, moulds and mushrooms start growing and consuming every part of the dung. Parts of the mycelium and spores stick to the surrounding vegetation, are then eaten by the large herbivores, survive their journey through the digestive tract and start colonising the dung from within.

Plants profit too, because the seeds that are consumed by grazers often survive the alimentary canal and kickstart their growth supported by dung nutrients.

Eventually, snails and slugs, centipedes, millipedes, woodlice, nematode worms and earthworms invade to decompose the cellulose debris that is left.”

Keeping grazing areas medicine-free

Most nature managers in the Netherlands have a policy that only allows untreated grazers in their nature areas. This is easy to achieve when they hire companies that only work with semi-natural grazers. These companies are well aware of the natural functioning and resilience of such grazing populations.

To reduce management costs, however, more and more nature managers are cooperating with farmers for the grazing of their areas. Some farmers even pay nature managers for using the land, contributing directly to the income of nature organisations and improving cooperation with their direct neighbours. In some cases, a ban on using medicines is included in lease contracts with farmers. But despite such legalities, dung often remains untested, which means it is possible that some animals are still treated before their release.

A major obstacle to the implementation of testing is cost: an individual test to check whether there are medicinal residues in dung is very expensive. So even though many nature managers are now well aware of the value of clean dung and therefore highly motivated to keep their areas clean, such tests are rarely done. It is even rarer for farmers or other herd managers to be reprimanded when found to be breaking the rules.

Pragmatic as always, ARK has fortunately found a solution for this: when run in very high numbers, tests are far cheaper. By cooperating and running tests together, nature organisations can reduce the cost of each test by 25%. We hope to start running tests this spring, at the same time as cattle and horses are introduced to nature areas. In partnership with farmers and herd managers, testing can thereby help us to keep grazing areas as medicine-free as possible.

The insect crisis can be mitigated step by step. We hope and expect this small step to make a meaningful contribution. Go visit a nature area near you and check out that shit!

This blog is created as part of GRAZELIFE, a project that evaluates the benefits of various land management models involving domesticated and wild/semi-wild herbivores. The project is carried out at the request of the European Commission. The GRAZELIFE Consortium gathers information with literature reviews, interviews with more than 100 stakeholders and field research in 8 European regions (encompassing 11 European countries). With these series of blogs the 10 Consortium-partners are sharing experiences and insights, that could contribute to a fruitful discussion on best practices in grazing systems.