The new German study is good news for bear conservation in Europe, but has implications for rewilding and the mitigation of human-wildlife conflict.

Great expectations

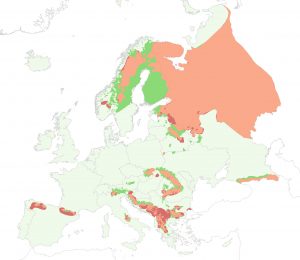

A recently released pan-European study by the Leipzig-based Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) shows that there are many areas of Europe which boast habitat suitable for brown bear recolonisation. While bears are currently missing from these areas – estimated by the study to cover 380,000 square kilometres – beneficial management of the species, such as a reduction in hunting pressure, would help Europe’s largest carnivore make a comeback here.

Around 500 years ago brown bears existed almost everywhere in Europe. Since then their population has declined, mainly as a result of hunting and habitat loss, and they have disappeared from many countries. Today the European brown bear population numbers roughly 17,000 animals, distributed between ten separate populations across 22 countries. Some of these populations – such as the Marsican brown bears of the Central Apennines rewilding area in Italy – are at risk due to their small size.

Alexandros Karamanlidis, a regional manager for Rewilding Europe, says he wasn’t surprised by the results of the study.

“The facts speak for themselves,” says Karamanlidis. “Bear populations are currently expanding in almost every European country where the animals exist. The reasons for this comeback are complex, but if there wasn’t any suitable habitat this expansion simply wouldn’t be happening.”

With attitudes toward large carnivores now shifting in Europe, the fact that there is still suitable European habitat for brown bears to recolonise is a good news for the conservation of this majestic animal. However, the new study does have implications for the management of the species.

“I think the main takeaway is that we should expect and plan for bears come back to areas of their former range,” says Karamanlidis. “Obviously bears don’t recognise international borders. This means conservation efforts should be on a transborder scale.”

As carnivores continue to make a comeback in Europe, people and predators are increasingly coexisting in the same landscapes. However, this coexistence is not without its challenges.

“Preemptive action is a hugely important when it comes to mitigating conflict between bears and humans,” says Karamanlidis.

In potential bear recolonisation areas such action includes raising people’s awareness and generating goodwill towards the animal, helping people to protect their property, and, in some cases, leveraging opportunities to develop sustainable, bear-based tourism. It should be noted that direct attacks by bears on humans are extremely rare, with the animal generally trying to avoid people.

The rewilding context

With its large cities, modern infrastructure network and extensive areas under intensive agriculture, Europe seems an unlikely place for a large carnivore comeback.

But despite this, a 2011 study commissioned by Rewilding Europe from the Zoological Society of London (and partners) found five European carnivore species – the brown bear, Eurasian lynx, wolverine, grey wolf and golden jackal – all expanding their range. In many areas of the continent, these animals are surviving and increasing outside protected areas.

“This comeback, especially with regard to bears and wolves, shows the amazing resiience of these animals,” says Karamanlidis, who has been involved with the study of bear populations in Greece and across Europe for nearly 20 years. “Populations are returning in a human-dominated landscape.”

The arrival of large carnivores in European habitats where they were previously absent is having both an ecological and social impact. As these animals come into closer contact with humans, some conflict is inevitable.

In the past, predation of livestock by carnivores was a major contributory factor in their decline. Such predation is often a symptom of depleted natural prey populations.

“The weakest link in the European carnivore comeback is large herbivores,” says Karamanlidis. “One of the reasons Rewilding Europe is working so hard to reintroduce animals such as red deer and bison, which were removed by man, is to boost the natural prey base for carnivores.”

Karamandlidis says the results of the new study have implications for Rewilding Europe across many of its operational areas. In four of these areas – the Velebit Mountains, Central Apennines, Southern Carpathians and Lapland – brown bears are a resident species, while bears have also been spotted in the Rhodope Mountains.

“Our rewilding work is typically based on the current status of individual species,” says Rewilding Europe’s regional manager. “But this study shows that bears are likely to push into new territory as they continue their comeback. This means that we need to plan for such territorial expansion, both in terms of protecting more habitat and in anticipating potential conflicts.”

Putting opportunities into a local context is vital to sustain carnivore comeback in Rewilding Europe’s rewilding areas. In the Central Apennines rewilding area, for example, Rewilding Europe and local partner Salviamo l’Orso are already carrying out a range of measures to preempt conflict between Marsican brown bears and local residents.

The results of this study are also relevant to members of Rewilding Europe’s burgeoning European Rewilding Network involved in bear-related work, such as the LIFE DINALP BEAR project and the Carnivores.cz initiative.

- Lean more about Rewilding Europe’s work and involvement with large carnivores here.