This joint initiative aims to expand the European bison population in the Southwestern Carpathians and ensure its long-term persistence by enabling successful coexistence through a national bison plan and “bison-smart communities” that are learning to life alongside Europe’s largest free-roaming land mammals once more.

The story of bison in Europe

The comeback of the European bison is one of Europe’s most heartening wildlife recovery stories. Once widespread across the continent, this magnificent animal was driven to the edge of extinction in the early twentieth century by hunting and habitat loss.

When the last wild European bison was shot in the Caucasus in 1927, there were less than 60 individuals alive in zoo and private parks. From the 1950s onwards, European bison began to be reintroduced back into the wild.

An unlikely Comeback

It is from this low point that the European bison has slowly but surely inched its way back, supported by various breeding programmes and reintroductions, with the first bison released back into the wild in Poland’s Białowieża Forest in 1954.

Over the last 10 years the estimated number of free-roaming European bison has increased from 2579 to around 8000 individuals, with the largest herds found in Belarus and Poland.

10 years after the first release in the Țarcu Mountains (2014), the population counts 194 free-roaming bison. 14 bison have already been translocated in the frame of the new LIFE with Bison project by Rewilding Europe, WWF Romania, Rewilding Romania, WeWilder, Research and Development Institute for Wildlife and Mountain Resources, and Municipalities of Armeniș, Teregova and Cornereva.

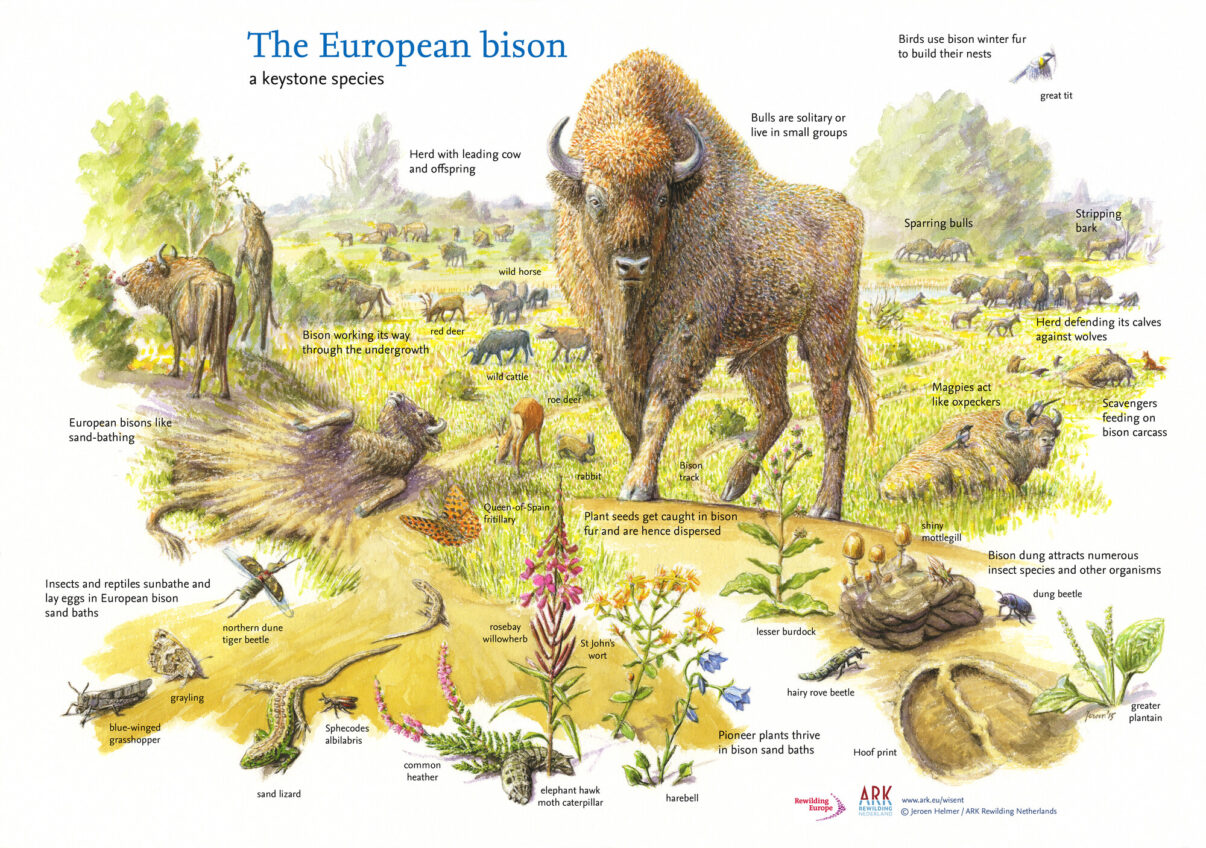

The European Bison – A keystone species

The European bison is a keystone species since it plays a distinct ecological role in shaping the landscape it inhabits. In addition to consuming significant quantities of grasses and feeding on shrubs, bison influence the vegetation by de-barking trees, breaking open dense undergrowth (simply by walking right through it), and creating bare soil patches (by wallowing), which allows pioneer plants to move in. In addition, bison disperse nutrients (dung) and seeds across their territory (they scatter over 200 species of plants, which helps to increase floral biodiversity and supports pollinators). Breeding birds use bison winter fur as nesting material, and magpies follow the bison herd to pick off ticks and other parasites.

In the Southern Carpathians rewilding landscape, the reintroduced bison are already helping to create and maintain a half-wooded, half-open landscape, with the animals grazing excess vegetation from forest openings, meadows and forested meadows. As the diversity of the landscape and vegetation increases, so a range of habitats are created that are suitable for other grazers, small mammals, birds and invertebrates. In this way, bison conservation has wide-ranging ecological benefits for the entire region.

Objectives

Setting the base

Ensuring effective and result-oriented implementation of the intervention through management and coordination.

National context

Prepare a national Strategy and Action Plan and create an enabling environment for the management of wild bison in Romania.

Growing the population

Grow and expand the range of the bison population in the Țarcu Mountains by translocating at least 40 individuals.

Supporting coexistence

Empower local people to mitigate potential conflicts through new governance and intervention models.

Supporting business

Create livelihood opportunities for local people and communities from the bison’s comeback to the region.

Engage

High-quality engagement and public awareness that showcases coexistence success and the benefits of the bison’s comeback.

Monitor and analyse

Keep track of achievements and impacts of the overall intervention and analyse its results in preparation of dissemination.

Sharing knowledge

Inspire and support others to replicate success and expand the bison population in the Carpathians.

Beneficiaries

Funding Partners

Disclaimer: “Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or CINEA. Neither the European Union nor CINEA can be held responsible for them.”